Pages

30 October 2020

Denver Ballot Issues For 2020 In A Nutshell

Colorado Ballot Issues For 2020 In A Nutshell

28 October 2020

The Electoral College Enhances The Risk Of A Contested Election

One of the best arguments for the Electoral College, I would have thought, was that it reduced the risk and impact of a contested election.

After all, you basically can't have and will never need a national recount in the Electoral College system, only recounts in a handful of states with close outcomes that also happen to be marginal states in terms of the required 270 electoral vote majority, a national recount seems awful, and two party systems naturally tend to develop coalitions in which each side has close to a 50% chance of winning.

But recent research casts some doubt on that intuition. As the Marginal Revolution Blog explains, citing recent social science analysis of the issue:

Starting from probabilistic simulations of likely presidential election outcomes that are similar to the output from election forecasting models, we calculate the likelihood of disputable, narrow outcomes under the Electoral College. The probability that the Electoral College is decided by 20,000 ballots or fewer in a single, pivotal state is greater than 1-in-10. Although it is possible in principle for either system to generate more risk of a disputable election outcome, in practice the Electoral College today is about 40 times as likely as a National Popular Vote to generate scenarios in which a small number of ballots in a pivotal voting unit determines the Presidency.

And note this, which explains a good deal of the debate and rationalizations — on both sides:

This disputed-election risk is asymmetric across political parties. It is about twice as likely that a Democrat’s (rather than Republican’s) Electoral College victory in a close election could be overturned by a judicial decision affecting less than 1,000, 5,000, or 10,000 ballots in a single, pivotal state.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Michael Geruso and Dean Spears.

Further Analysis

Evaluating Contested Election Risk Well Is Possible

Election administration is essentially identical in any statewide election. The election administration issues would be identical, in any given state, under the Electoral College and under the popular vote system.

And, we have all sorts of experience with the risk of a contested election in an Electoral College system and in other statewide elections.

The analysis of a risk of a close election in a popular vote system should be much simpler. You add up the poplar vote totals from each state and you compare them. If they are sufficiently close, it is viable to mount a serious contest to the result. If the gap between the major candidate vote totals is significantly more than historical change in the outcome from each respective state's contested election outcomes, a contest isn't viable. If it the margin of victory is within the historically precedented margin of error of the vote count in 50 collective statewide elections and the DC election, then a contest is viable.

The overall national popular vote outcome is well predicted by a simple national polling average of likely voters, something we have exhaustive data upon.

It is more cumbersome to get, but nothing but hard work separates a research from excellent quality historical data on the margin of error revealed in contested elections.

And, the margin of error isn't very strongly sensitive to modest changes in the proportion of voters favoring each candidate in a particular state. Your margin of error estimate in a state gains an uncertainty of only about 10% with a five percentage point error in the proportion of voters who favor a particular candidate, which is a pretty big and unusual error (bigger than the polling errors in the swing states in 2016).

Four Potential Flaws In The Paper

I don't have access to the body text of the paper and my main concern about it are fourfold.

First, it seems to be evaluating contest viability based upon raw vote differences in absolute terms when the appropriate measure is the percentage difference. A 20,000 vote gap nationwide out of 150,000,000 votes cast is worth contesting. A 20,000 vote gap out of 450,000 votes cast in New Hampshire to determine who won its electoral votes is not.

Second, it isn't clear if the study considers the impact of a contest in the respective cases properly. Even if it is rare, a nationwide recount in 50 different states and DC, each using different election administration systems, is a huge deal. A recount in two or three U.S. states that are potentially decisive in the Electoral College result is less disruptive and has far less moving parts to try to get right. Moreover, in the Electoral College, even if the state SOS certifies the wrong slate of delegates, once it is done, it is done. The Congress counts the ballots sent to it by the certified delegates than that is that, because the delegate votes (which have a discretionary element) and not the vote totals, is what Congress is counting.

Third, it isn't obvious from the abstract that they are considering the fact that recount outcomes in Republican administered jurisdictions, and in Democratic administered jurisdictions, respectively, are likely to be strongly correlated, because the raise the same kinds of issues and administer their respective elections in similar ways.

Fourth, another important point is that in any given election, a contests will tend to happen with one method, or the other, but not both. This depends upon the national vote share of the candidates relative to each other, which, in turn, is largely a function of turnout.

In a year where a small number of votes in a few marginal states decide the Electoral College outcome, like 2000 or 2016, the popular vote is not going to be remotely close (the Democrat will lead by several million votes) and turnout will be moderately high.

In extremely high turnout years, Democrats win the Electoral College too without close races in the marginal state and contested elections are unlikely period.

In a year where the popular vote is down to the wire, the Electoral College will be a clear win for the Republican with the marginal state having a several percentage point lead for the Republican, and turnout will be moderately low.

In extremely low turnout years, Republicans win the popular vote too and contested elections are likewise unlikely.

All other things being equal, a popular vote system should increase voters turnout relative to an Electoral College system, because it increases the relevance of the voting for both parties in states that are safe one way or the other for one party. So, a popular vote system itself, by increasing the likelihood of higher turnout than in an Electoral College system, reduces the likelihood of a contested popular vote outcome - at least until the candidates recalibrate their coalitions and messages to reflect the absence of the pro-Republican bias of the Electoral College.

Also, within that higher overall turnout range, turnout should be higher in years where national, general election polling is tight, and should be lower in years where national general election polling shows a clear favorite.

Does The Overall Conclusion Still Make Sense?

The hypothesis is still pretty plausible despite these concerns. Why?

It is almost guaranteed in an Electoral College system that one or several states will have an outcome that is close enough to contest, and candidates have a natural tendency to adjust their coalitions and approaches to match that tipping point. If any of those states are marginal or potentially marginal it makes sense to contest the election.

But, in a popular vote scenario, the actual popular vote margin of victory has to be less than about 0.5 percentage points nationwide to be worth contesting, which isn't all that common historically (although the candidates would drift in their appeals towards that equilibrium if a popular vote system were adopted).

Also, in a national popular vote system, there is a greater incentive for politicians nationally to insist on running a tighter ship in terms of election administration than they would now in a safe state where close partisan elections are rare in jurisdictions like DC or MA or AL or UT. This should reduce the margin of error that a recount or contest can produce relative to the status quo.

Not All Contested Elections Are Equally Important

One final thought.

The main axiom that justifies the electoral process in Presidential elections (although not the only one, even one party states find it useful to hold national Presidential elections) is that a Presidential election in which essentially all voters in the country participate is the best way to select the candidate who is most likely to act in the best interests of a majority of voters as those voters weight their concerns and priorities, among the candidates that are available for voters to choose from in the electoral process.

But there is no guarantee that the voters will make the right choice in any given electoral process. Some electoral processes may lead to the right choice more often than others, but the voters can make the wrong choice - not primarily because they are wrong about what their best interests are (although voters can get carried away with hype and misconceptions like anyone can), but because they are wrong about what the candidates will actually do if elected or what the consequences of those actions will be.

The closer the popular vote is in an election, the less important, in some abstract philosophical sense, it ought to be to have the election administration selection the correct winner.

If 75,001,000 people vote for Candidate A and 75,000,000 people vote for Candidate B, the general public really has no idea who is the better candidate, perhaps because it is not possible to know with any accuracy. In an outcome like that, we are getting into questions of spurious precision in the electoral process, given the limited capacity of the voters to accurately determine which candidate will be better.

The likelihood that the median voter made a bad decision in this scenario on the merits, for example, due to cognitive biases or campaign flourishes that don't reflect on likely actual performance on the job, far exceeds the risk that the vote count is masking an accurate determination by the voters of the best candidate based on something more than random chance.

If the popular vote is that close, either candidate is probably fine.

In contrast, the Electoral College, as it currently exists, has a built in three percentage point Republican bias, and the potential to be significantly worse than that in not particularly improbable possible outcomes.

So, it is very hard for even a much higher precision determinations of the Electoral College winner under the Electoral College rules to outweigh that fact that the more precise the outcome is the more certain it is that it is systemically biased from choosing the right candidate.

Overall, the Electoral College is much more likely to choose the wrong candidate to be President.

Supporting that conclusion, it is hard to conclude that the Electoral College made a better choice than the popular vote in any of the recent elections in which these measures reached difference conclusions. QED.

The Army's Future In East Asia And Larger Related Trends

An op-ed on military affairs in a military oriented specialty journal argues that for the near future, China is a bigger concern than Russia, militarily, and discusses what this shift in mission and technological change mean this will look like.

Overall, I think the authors, David Barno and Nora Bensahel, on the right track, so I restate a substantial chunk of their analysis below (italics in the original, bold emphasis mine, paragraph breaks inserted to suit the blog format's reading needs):

During the Cold War, the U.S. Army formed the bulk of NATO forces postured to deter or defeat a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. It also provided most of the forces that served in Korea, Vietnam, the 1991 Gulf War, and more recently, Iraq and Afghanistan. The Army has grown accustomed to being what’s called the supported service, where the other services help enable its land operations.

Yet the explicit prioritization of China over Russia means that this relationship is about to flip. The Army will be a supporting service in any potential conflict with China, tasked with enabling the other services in a conflict that would span the vast air and maritime domain of the Western Pacific. . . .

Its ground combat forces will remain essential for deterrence (and, if necessary, fighting) on the Korean peninsula, but otherwise its role in the Western Pacific against China will remain limited. Yet despite this shift, the Army is planning to conduct littoral operations throughout the region that in many ways duplicate missions the Marines have traditionally performed, and updated in their most recent doctrine and Commandant’s Planning Guidance.

Instead of competing with the Marines for a major role in the littorals, the Army should instead focus on providing critical enablers to the rest of the joint force in the Pacific. These include capabilities like land-based air and missile defense, theater-wide logistics and engineering, electronic warfare, and potentially, long-range precision fires. The service’s new Multi-Domain Task Forces, with their integrated cyber, space, fires, and electronic warfare functions, may also provide other innovative capabilities to the Pacific fight that could be more useful than maneuver forces.The Army’s traditional ground combat capabilities will still be required in Europe. Russia remains the most capable and dangerous potential U.S. adversary in the land domain, and U.S. Army forces will still be required to defend Europe from Russian aggression and buttress NATO’s defense. But those missions, which were the main U.S. strategic priority for many decades, are now a lower national priority than deterring and possibly fighting Chinese aggression in the Pacific. The fact that the Army’s primary combat mission is now a secondary national security priority will pose enormous challenges for the service, including almost certain cuts to Army force structure and end strength, and present an uncomfortable degree of risk in the European theater.The Shift from Maneuver to FiresFinally, the Army is being disrupted by the changing relationship between fires and maneuver, as both weapons technology and the importance of long-range precision fires in future conflicts rapidly advance. Traditionally, the Army has devoted a sizable part of its end strength to maneuver units — primarily the infantry, armor, and cavalry formations that assault the enemy and seize and hold terrain — and relied on fires from artillery and rockets to support those maneuver forces. But the advent of precision long-range fires is inverting this traditional relationship. Traditional artillery used to support maneuver troops generally has a range between 15 and 25 miles. Today, land-based precision rockets and missiles are being developed with potential ranges of over 1,000 miles.This unprecedented technological leap-ahead is completely altering the roles of fires and maneuver. For the first time, land forces will be able to strike adversaries at strategic ranges without having to utilize nuclear weapons — and that means that they might be able to deliver strategic effects. In the near future, the Army may be able to use precision long-range fires to shatter adversary units, command and control networks, and vulnerable logistics and supply routes. The Army’s main contribution to a future war in the Pacific could soon involve using these new and powerful weapons to strike a wide range of naval and island targets, without utilizing its maneuver forces at all.

The bottom line is that the Army's main missions in East Asia are launching relatively long range precision missile strikes from land based launchers, and operating land based missile defense systems.

* The authors don't spell out the point, but this isn't just because Russia is a declining power, while China is a rising one. It is also, and to a greater extent, a question of our objectives.

What the Army and Marines can do, that the Air Force and Navy cannot, is hold territory on land. In Europe, Central Asia (i.e. Afghanistan), and the Middle East (and before that in Vietnam and Korea), holding territory was a key objective of military action.

But, the U.S. and its allies have no desire to hold or control territory on land in China. It isn't that American troops couldn't hold territory on some intrinsically irrelevant islands in off of China's coast. It could. Instead, the current effort is to deny China monopoly control over maritime territory needed for international shipping, and to a lesser extent to legally exclude foreign military vessels, for fishing, and to exploit underwater mineral resources. The largely barren and undeveloped islands interspersed within those seas are relevant only as a quirk of somewhat obsolete diplomatic and international law rules.

The shift in the Army's role does recapitulate a few key points I've been making, more or less loudly, and more or less repeatedly, which I'll restate here:

* Slug throwers with slugs big enough to be called "shells" have been technologically surpassed across the board by missiles and "smart bombs". Missiles are now more accurate, have longer ranges, come in more sizes to suit particular needs, and perform better in lethality to relative to the combined weight and bulk of the munitions and their delivery systems, right down to systems carried by infantry in light vehicles. Missiles cost more per round than shells, but the hottest conflicts anywhere in the world by any military force in modern times delver few rounds in anger, higher accuracy compensates for some of the discrepancy, and much of the cost disadvantage of missiles involves intellectual property royalties for guidance system patents that are well on their way to expiring and dramatically lowering the per unit price of missiles.

* Active defenses (like surface to air missiles (SAMs), Patriot missile defense systems, a land adapted version of the Navy's Close In Weapons System, and directed energy weapons, i.e. high voltage lasers, to take down incoming missiles, shells, and drones) now predominate over static armor. The Marine Corps is getting out of utilizing tanks entirely, which is a wise move. There is almost no bunker that a suitable missile or bunker buster bomb that can be delivered by aircraft can't defeat.

* Institutionally it makes less sense than it ever has to maintain a separate Army and Air Force. Donald Trump's creation of the "Space Force" was a step backward. The Army and Air Force are more interdependent than they have ever been and making a top level bureaucratic segregation of our military resources on this obsolete basis didn't make sense in the 1970s in Vietnam, and makes even less sense now.

The necessity case for 1,000 mile range Army missiles is pretty silly, when the Air Force has that problem well in hand already. If the Army and Air Force were integrated:

* we wouldn't have forced engaged in duplicative procurement efforts to develop long range precision strike capabilities,

* we would be using rugged short takeoff and landing fixed wing aircraft rather than utility helicopters in many roles where helicopters are the vehicle of choice despite having inferior capabilities for the mission because Army generals can control them rather than asking another military service for backup;

* the Air Force wouldn't have spent the last 30-40 years underinvesting in close air support and Army transport missions, and overinvesting in bombers and air to air combat missions to the same extent that it has; and

* integration of Army forward observers calling in strikes and Air Force resources delivering them would been more seamless and would have happened sooner.

An aside:

The U.S. military has immense fraud, waste and abuse, as the largest bureaucracy at any level of the United States government that is larger and far more complex than any private U.S. corporation. But the big dollars of defense funds misspent come from unclear or unwise priorities at a strategic level (most military procurement simply seeks to replace what is worn out or outdated on a one to one basis with new versions of basically the same things, without really revisiting why and whether we need them) and technological bad decisions, that require thoughtful and hard choices at the top to address, not diligence in rooting out corruption and mid-level incompetence at the Pentagon and in defense contractors. We need more of some things, but much less of others than we are buying.

27 October 2020

Redrawing State Lines For Fairness And Greater Political Harmony

Map from here.

Twelve Constitutional Amendments Worth Considering

The following twelve constitutional amendments would be an improvement and, if proposed, might actually pass with bipartisan support.

These aren't the only aspects of the U.S. Constitution which I'd like to change (e.g. repealing the Second Amendment), but these are all likely to be adopted with wide bipartisan support if this proposal are seriously advanced.

Each proposal is designed to stand alone, but it might be desirable to propose them as a package similar to the twelve amendments in the original Bill of Rights ten of which were adopted right away and one of which was adopted much later.

Coming up with a name for the package is hard because a "Democratic Bill of Rights" would cause many uninformed people to think it was about the Democratic party and not little "d" democracy. Perhaps the "Fair Politics Amendments" might do the trick.

The process by which constitutional amendments are proposed and adopted is set forth in Article V of the U.S. Constitution:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Providedthat no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; andthat no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

No prior amendment has been ratified in state conventions, but I would propose that the most fruitful approach would be to have Congress propose this package and for the package to be ratified in state conventions, rather than by state legislatures, which may be the most resistant to legislation loosening up the political status quo that they benefit from themselves.

1. Lame Duck Legislation

Proposal

After election day in an even numbered year, require any legislation passed to receive a two-thirds majority of both the House and the Senate, and require any nominee proposed to the U.S. Senate for confirmation to receive a two-thirds majority (effective for the first session of Congress after it is adopted).

Analysis

This is a common sense measure that many people would easily favor, given the obvious and historically precedented risk of abuse by lame duck congress.

2. Ending The Electoral College

Proposal

Elect the President of the United States by a direct popular vote conducted in a manner provided by law. If no candidate receives a majority in a direct popular vote, hold a runoff election between the two candidates receiving the most votes in the direct popular vote, held on the first Tuesday after the second Monday in December. The right to vote in this election would extent to all American citizens without regard to place of residency. Other aspects of eligibility to vote would be established by Congress subject to existing constitutional standards for the franchise. This would take effect in the first Presidential election held after it is ratified. Jurisdiction over the administration of elections in each state and litigation over state election administration, including vote counting, would be vested exclusively in the state courts of that state subject only to U.S. Supreme Court review, with the conduct of federal elections outside of U.S. states governed by federal law. In the highly unlikely event of a tie vote, the winner would be determined by random chance.

Analysis

Despite naive political logic, this proposal has roughly 70% support in the population at large, strong bipartisan support in every U.S. state even in small and conservative states that would see their clout in Presidential elections reduced, for example, 69% support in Wyoming, 70% in Alaska, 72% in Montana, 75% in Vermont, 74% in Rhode Island, 81% in West Virginia, 67% in South Dakota, and 66% in Utah.

Notably, both major U.S. political parties give party members who reside in places that do not have electoral votes, such as U.S. territories and "Americans abroad" a say in their party's Presidential nomination process.

Of course, it would need to be ratified by only 38 states (39 if D.C. or Puerto Rico or both were admitted as states), and the percentage of popular support in the 38-39 states where support is strongest in polls would be even greater.

A two round system in the event of a spoiler candidate is preferable to ranked choice voting because it is easier to administer, does not require voters to engage in hypothetical thinking, and allowed for further time for voters to be informed about candidates in close or indecisive elections which voters favoring a candidate who is eliminated in the first round might not engage in otherwise.

A two-round system is used to elect the presidents of 48 countries (out of 61 other than the U.S. that have Presidents at all): Afghanistan, Argentina, Austria, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, East Timor, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, France, Finland, Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Iran, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Liberia, Malawi, Moldova, North Macedonia, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Togo, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay and Zimbabwe.

Instant runoff voting is used in Presidential elections only in the Republic of Ireland.

Most other twelve countries with Presidents, in the cases where they directly elected at all (in some of these countries the parliament selects the President), use plurality voting as the U.S. does, which is subject to spoiler effects that the a two dominant party Presidential primary system partially, but not completely mitigates.

3. Congressional Term Limits

Proposal

Limit U.S Senators to two terms (a partial term counts if it is three or more years), and representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives to six terms (a partial term counts if it is one or more years), after the amendment is ratified.

Analysis

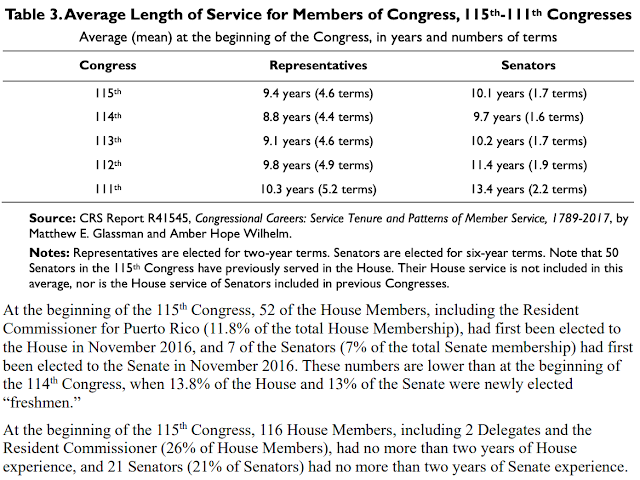

At the beginning of the current 115th Congress, the average length of service for Representatives at the beginning of the 115th Congress was 9.4 years (4.7 House terms); for Senators, 10.1 years (1.7 Senate terms). So, while this proposal would shorten the average tenure in Congress over time, it wouldn't do so in all that radical a fashion.

Note that the maximum combined service in Congress under this proposed amendment is still 24 years in ordinary cases, and up to almost 28 years considering vacancy appointments. The amendment would apply with even less force to incumbents at the time the amendment is ratified, but it would mitigate undue incumbency effect in U.S. House and U.S. Senate elections in the long run.

A national poll in 2018 found that 82% of Americans favor term limits for Congress.

4. Require Majority Support For Election To The U.S. Senate

Proposal

If no candidate receives a majority in a direct popular vote, hold a runoff election between the two candidates receiving the most votes in the direct popular vote, held on the first Tuesday after the second Monday in December.

Analysis

This would eliminate third-party spoiler effects in U.S. Senate elections. Some states, but not all, already have this requirement. It would be better not to extend this to Congressional elections to leave open the option of proportional representation in those elections.

California, Louisiana, and Washington State use a blanket primary two round system in which all candidates from all parties compete in a single first round election (not proposed to be mandated by this amendment) that has this effect, because a first round winner, or a second round winner, if necessary, must secure a majority of the votes cast.

Georgia has a majority vote to win requirement combined with partisan primaries.

Arguably, this could be done by law, rather than by constitutional amendment, pursuant to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution which states:

The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.

5. Grounds For Impeachment

Proposal

Expand the grounds for impeachment from "high crimes and misdemeanors" to include incapacity, incompetence, failing to faithfully execute the laws, and receipt of unconstitutional emoluments, effective after the first Presidential election following its ratification.

Analysis

The grounds for impeachment are nonjusticiable but the symbolic and rhetorical effect would probably be to make Presidents more accountable to Congress. It would leave in effect the two-thirds majority requirement to remove a sitting President who has been impeached from office.

Notably, both a Democratic President (Bill Clinton) and a Republican President (Donald Trump) have faced a recent, unsuccessful impeachment attempt.

6. Campaign Finance

7. Congressional Representation In U.S. Territories

Proposal

Give any self-governing district, commonwealth, or territory of the U.S. the number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives that it would have if it was a state. Thus, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam and the U.S. Mariana Islands, would each get one seat in the U.S. House.

Analysis

Do this promptly after granting D.C. and Puerto Rico statehood as part of an amendment to repeal the 23rd Amendment. This way, states know that if the amendment is not ratified, that these territories might be granted statehood. and that a rump D.C. including only the core capitol area of D.C. would still have three electoral votes.

It is fundamentally unfair that any U.S. citizens who live in the U.S. and are subject to its laws should be denied the right to have any say in the making of its laws. Congress already gives each of these jurisdictions non-voting commissioners in the U.S. House.

The dilution in the power of existing states in the U.S. House of Representatives would be less than 1% if this occurred after the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico gained statehood, and less than 3% if they did not, and the percentage dilution could be reduced by increasing the number of seats in Congress which may be done without a constitutional amendment.

8. Judicial Term Limits

Proposal

Limit Article III federal judges and justices (including but not limited to the U.S. Supreme Court) appointed after the effective date of the amendment to 16 years of service in any one appointment, in lieu of the current lifetime appointment, and bar judges and justices from serving as "senior judges" after their term of service expires. The average term of service of non-incumbent U.S. Supreme Court justices in U.S. history is just under 17 years.

Analysis

There is 77% support in polls for term limits for lifetime appointment judges. This would also reduce the incentive to appoint very young, unproven justices to high judicial office.

9. Requiring Bipartisan Support To Confirm Judges

Proposal

Require all appointments of Article III Justices to receive a 60% majority on the merits in the U.S. Senate to confirm their appointments, and eliminate recess appointments of Article III justices.

Analysis

Sixty percent tactic support was the de facto requirement under U.S. Senate rules for U.S. Supreme Court appointments until 2017, so the case for making the change now that didn't exist before is strong. Most people, even with high levels of civic awareness, don't even know that recess appointments of judges are possible (or for that matter that recess appointments of any kind are possible).

History shows that justices who receive less than 60% support in the U.S. Senate tend to be extremists, while the requirement of at least some bipartisan support would lead to more moderate judicial appointments. For example, prior to the Trump Presidency, no SCOTUS justice was confirmed without a filibuster proof majority to vote (60 votes in recent years and a two-thirds majority before that) on holding a vote.

Gorsuch was confirmed by a 54–45 vote. Kavanaugh was confirmed by a 50-48 vote. Barrett was confirmed by a 52-48 vote. None of them would have survived a filibuster.

Alito and Thomas got past the filibuster, but Alito confirmed by a 58-42 vote and Thomas was confirmed by a 52-48 vote.

In contrast, Roberts' confirmation vote was 82-22, Sotomayor's was 68-31, Breyer's was 87-9, and Kagan's was 63-37.

This would reduce the rate at which judges rated unqualified are confirmed to essentially zero, without affording the American Bar Association any formal constitutional or statutory power.

Unqualified judges and extreme judicial partisanship that the status quo encourages undermines the authority of the judiciary and the long term stability of the country as a constitutional democracy.

10. Fixing The Size Of The U.S. Supreme Court

Proposal

After increasing the size of the U.S. Supreme Court to 13 justices in a Biden Administration (resulting in a 7-6 liberal majority on the U.S. Supreme Court) without a constitutional amendment, propose a constitutional amendment to fix the size of the U.S. Supreme Court at 15 justices with the two additional justices to be appointed only after the next Presidential election. Also require an affirmative vote of eight justices would be required to reverse a lower court decision on the merits.

Analysis

This would provide an answer to the temptation to increase the size of the U.S. Supreme Court every time you don't like its composition while leave the question of a liberal or conservative majority in the hands of the President elected after the amendment is ratified. A larger court, ideally with term limits, would make U.S. Supreme Court appointments more common and more evenly spaced, while reducing the stakes of any one appointment. Also, if bipartisan confirmation requirements were adopted, the more moderate mix of judges on the high court would reduce the stakes that brought us to the current crisis where conservative extremists have a majority on the high court.

11. Presidential Qualifications

Proposal

Eliminate the "natural born citizenship" requirement for Presidential candidates. As follows:

No Person excepta natural born Citizen, ora Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution,shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

Analysis

This constitutional provision is the only one in the U.S. Constitution or law that makes a distinction between "natural born" citizens, naturalized citizens and possibily other citizens who are neither "natural born" nor naturalized citizens. It is ill defined. It has ruled out, or cast unproductive, anti-democratic doubt on multiple well qualified attractive U.S. Presidential candidates in both major political parties for a reason that shouldn't matter, for example, Henry Kissenger, Arnold Schwarzenegger, John McCain, Ted Cruz, Barack Obama, Marco Rubio, Bobby Jindal, Tulsi Gabbard and Kamala Harris.

This amendment is no strong partisan valiance. Prominent and popular politicians in both political major political parties would benefit from the proposal.

12. Gerrymandering

Proposal

Authorize Congress to establish by law standards for drawing Congressional districts, or other election law reforms, to better align the collective outcome of elections for the U.S. House of Representatives in a state with the proportionate partisan preferences of the people in that state, that are thwarted by gerrymandering, and to enforce the laws enacted pursuant to this Amendment.

Analysis

This doesn't proposed to solve the problem of gerrymandering, which is non-obvious, but provides a mechanism for a national solution to be developed which U.S. Supreme Court decisions declining to address partisan gerrymandering such as the 2019 decision of Ruccho v. Common Cause, largely preclude.

There is strong bipartisan support for ending or reducing gerrymandering.

Allowing Congress to address gerrymandering by law shouldn't be too controversial in principle, and it is a collective action problem that takes national action, because a party strong in one state otherwise needs to gerrymander ruthlessly to counteract gerrymandering in the opposite direction in other states.

The Missions of the U.S. Military

The U.S. military has multiple missions, but for the most part, they are buried in jargon and euphemism. Much of this is done for the purpose of justifying force levels that don't really make sense with modern priorities.

Very little of the expense or focus is on defending the United States against invasion, either by land from Mexico or Canada, or by air and sea. Neither Mexico nor Canada has the capacity or inclination to do so, and the U.S. National Guard alone is probably up to the task of discouraging or defeating such an attempt. Russia could conceivably invade Alaska and likes to challenge U.S. airspace there, but has shown no strong impetus to seize Alaska. Neither Russia nor China nor any other country in the world that is not a strong U.S. ally has the military capacity to launch an amphibious or airborne assault on the U.S. with a significant number of ground troops. The U.S. Coast Guard is sufficient to keep pirates and smugglers in check.

The U.S. Department of Defense has a number of primary missions:

* Defending our allies (especially Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, New Zealand and Australia) from China and North Korea. This is primarily a U.S. Navy mission. The U.S. Army supports this mission from South Korean bases. The U.S. Marine Corps supports this mission from U.S. bases in Japan. The U.S. Air Force also supports this mission. All of these nations have advanced militaries of their own to assist in this effort, and the Philippines isn't entirely adverse to entering a Chinese rather than an American sphere of influence.

* The U.S. Army is charged with assisting our NATO allies in defending themselves against Russian aggression, although it declined to do so in the case of Russian seizure of territory in the Ukraine. The U.S. Air Force also supports this mission. Other NATO members have very advanced militaries of their own to assist in this effort. A Russian led invasion of Finland, Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Moldova, or Romania by Russian forces seems unlikely. Would NATO really step up to bat to defend Estonia, Lithuania or Latvia or Belarus? (None of which seems likely.) Also, Russia is considerably less formidable militarily than the Soviet Union was. It has barely more than half of the economic resources of the Soviet Union, has half the available conscripts, has seen a serious economic setback in the post-Soviet era, has had to devote resources to internal military conflicts, and has cut itself off from many of its key defense contractors by entering into military conflict with the Ukraine.

* The U.S. military might ally itself with Israel in defending Israel against attacks from its enemies but has not done so in multiple previous invasions. Israel has its own advanced military to assist in this effort.

* The U.S. Army had led regime change, peace keeping, and counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan, Bosnia, Kosovo, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Kuwait, Somalia, and various places in the African Sahel, sometimes with Marine Corps involvement as well. The U.S. Air Force also supports this mission. The U.S. Navy provides air bases and missile launching stations in support of ground operations by U.S. forces and our allies in the Middle East and North Africa.

* Defending the oil trade in the Persian Gulf from Iran. This is primarily a U.S. Navy mission. The U.S. Air Force has resources that could support this mission but is rarely tasked to do so.

* Preventing other countries (especially Russia and China) or pirates from interfering with civilian traffic (mostly freight) in international waters. This is primarily a U.S. Navy mission. The U.S. Air Force has resources that could support this mission but is rarely tasked to do so.

* The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are charged with evacuating Americans and our allies from war zones and disaster areas, and sometimes with providing additional disaster or humanitarian aid. The U.S. Air Force also has resources that could support this mission but is rarely tasked to do so.

* The U.S. military, while it has a long history of intervention in Latin America and the Caribbean has done so overtly only a few times in recent history, mostly briefly and sporadically, in Grenada and Panama. The U.S. Air Force has also supported this mission. This mission is not very central to U.S. foreign policy and military priorities.

It is fair to say that acquiring new U.S. territory through conquest is not a significant objective of the U.S. military.

Many of the places that are vulnerable to ground wars of conquest are places that the U.S. does not have a strong national interest in defending. Would the U.S. really care if there was another Iran-Iraq war? Would the U.S. intervene in a ground war invasion of Kashmir? Would the U.S. defend one Arab monarchy against another? The U.S. has shone no interest in intervening militarily in areas that are already under a de facto Russian or Chinese sphere of influence.

There is no likely scenario in which U.S. ground troops would have any sustained non-permissive presence in the territory of a non-allied nation in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, North Asia, or Central Asia.

There is no likely scenario in which U.S. troops conduct an amphibious invasion of a military near peer enemy nation. The only countries where an amphibious invasion of an enemy nation is plausible are countries that are decidedly inferior to the U.S. militarily.

While quite a few countries have "near peer" military capabilities, all but a handful of them are strong allies of the United States.