We examine the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on productivity in the context of taxi drivers. The AI we study assists drivers with finding customers by suggesting routes along which the demand is predicted to be high. We find that AI improves drivers’ productivity by shortening the cruising time, and such gain is accrued only to low-skilled drivers, narrowing the productivity gap between high- and low-skilled drivers by 14%. The result indicates that AI's impact on human labor is more nuanced and complex than a job displacement story, which was the primary focus of existing studies.

Pages

31 October 2022

AI Helps Noobs Most

28 October 2022

People Have Gotten Smarter, Patterns Of Decline With Age Are Unchanged

History-graded increases in older adults’ levels of cognitive performance are well documented, but little is known about historical shifts in within-person change: cognitive decline and onset of decline.

We combined harmonized perceptual-motor speed data from independent samples recruited in 1990 and 2010 to obtain 2,008 age-matched longitudinal observations (M = 78 years, 50% women) from 228 participants in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE) and 583 participants in the Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II). We used nonlinear growth models that orthogonalized within- and between-person age effects and controlled for retest effects. At age 78, the later-born BASE-II cohort substantially outperformed the earlier-born BASE cohort (d = 1.20; 25 years of age difference).

Age trajectories, however, were parallel, and there was no evidence of cohort differences in the amount or rate of decline and the onset of decline. Cognitive functioning has shifted to higher levels, but cognitive decline in old age appears to proceed similarly as it did two decades ago.

26 October 2022

The Aftermath Of Banning Non-Unanimous Jury Verdicts

The failure of the U.S. Supreme Court to make it landmark procedural ruling in Ramos v. Louisiana retroactive is so glaring that it is one of many rulings that undermines its legitimacy as an institution that vindicates justice.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared split-jury verdicts unconstitutional in 2020, in a ruling known as Ramos v. Louisiana.Oregon had been allowing split-jury verdicts since 1934, after a Jewish man accused of murder was convicted of a lesser charge because of a single juror holdout. Louisiana enshrined non-unanimous juries in its constitution in 1898, during a convention where the stated purpose was “to establish the supremacy of the white race in the state.”The Supreme Court ruling left it up to Oregon and Louisiana to figure out what to do with the hundreds of people already in prison for such convictions. On Oct. 21, Louisiana’s Supreme Court ruled against vacating those convictions, leaving the door open for the state legislature to take action. Oregon’s Supreme Court is similarly poised to rule on the issue, in an appeal . . . that could impact an estimated 250 to 300 other inmates in the state.

From here.

25 October 2022

A Good Candidate For SCOTUS Jurisdiction Stripping

Article III, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution provides that:

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

The U.S. Supreme Court also has broad supervisory jurisdiction over the lower federal courts apart from its appellate jurisdiction and its jurisdiction to hear cases in its original jurisdiction under the All Writs Act, adopted by the first Congress in 1789 and currently codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1651 which states:

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.(b) An alternative writ or rule nisi may be issued by a justice or judge of a court which has jurisdiction.

One of the things that the power to issue writs granted to the U.S. Supreme Court can be used for is to rule on interlocutory appeals (i.e. appeals of orders entered while a case is currently pending, rather than following its conclusion with a "final order") in extraordinary cases.

Justice Clarence Thomas recently did this to intervene in a grand jury investigation in a federal district court seeking testimony from a U.S. Senator in connection with alleged improprieties related to the 2020 Presidential election.

Justice Thomas stayed an order for Lindsey Graham to testify before a Georgia grand jury investigating the 2020 election. The October 24, 2022 order of Justice Thomas acting as a duty judge for the relevant judicial circuit states (in full):

Supreme Court of the United States No. 22A337

LINDSEY GRAHAM, UNITED STATES SENATOR, Applicant

v.

FULTON COUNTY SPECIAL PURPOSE GRAND JURY O R D E R

UPON CONSIDERATION of the application of counsel for the applicant, IT IS ORDERED that the August 15, 2022 order of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, case No. 1:22-CV-03027, as modified by the district court’s September 1, 2022 order, is hereby stayed pending further order of the undersigned or of the Court.Clarence Thomas

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

There is a very sensible argument that Congress should prevent this kind of intervention in trial court proceedings by removing the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court to issue writs in the nature of interlocutory appeals in U.S. District Courts.

Congress could instead limit that authority to the U.S. Courts of Appeals, which are the intermediate courts of appeal in the U.S. Court system, at least in the first instance as opposed to in appeals from another court's order in such an appeal.

This is what happens the vast majority of the time anyway. Justice Thomas' decision to intervene in this matter is extraordinary, even if it isn't entirely unprecedented.

Prior to the creation of intermediate federal appellate courts in the 1890s, when the federal court system was vastly smaller than it is today, this kind of intervention was fairly common and necessary because there was no one else to supervise trial court proceedings in this way. But in a vastly larger country with a vastly larger federal court system, this kind of meddling in the day to day workings of the federal trial courts starts to tarnish the U.S. Supreme Court as a political tool, as opposed to a forum focused on consistently upholding federal law in lower courts.

The U.S. Supreme Court should not be the court of first resort in trial court evidentiary and discovery disputes.

Quote Of The Day

I walked into the kitchen to get dinner, but all I found were ingredients.- Diane Dunn (October 25, 2022).

24 October 2022

The U.K. Has Its First Non-White, And First Hindu P.M., The Youngest In 200 Years

The Conservative Party in the U.K. (a.k.a. the Tories) is putting in a place a Prime Minister very different from its previous two incumbents in that position at a time when their party is in an abject crisis and has lost a great deal of public support for corruption during Boris Johnson's term, and for its inept economic policies.

Former finance minister Rishi Sunak will be the United Kingdom’s next prime minister after seeing off his lone remaining rival in the fast-tracked race to become Conservative party leader on Monday. . . .

Sunak will become the first person of color and the first Hindu to lead the UK. At 42, he is also the youngest person to take the office in more than 200 years. . . .

Sunak is set to replace Liz Truss, who will become the shortest-serving prime minister in UK history. Sunak will become prime minister once he is officially appointed by King Charles III and will be the first prime minister appointed by the new King following the death of Queen Elizabeth II in September.

From CNN.

Other Recent Notable Firsts For U.K. Prime Ministers

Liz Truss who served 44 days as Prime Minister in 2022 was the third woman to serve as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. She was proceeded by Theresa May who served from 2016 to 2019, and Margaret Thatcher who served from 1979 to 1990.

Sunak is not the first non-Christian to be a prime minister of the U.K., however (even ignoring religious conversions after leaving office).

Several prior Prime Ministers were non-religious and one may have been covertly Jewish even though officially he was an Anglican while serving as Prime Minister.

Twenty-Five Hot Legal Issues

I am a lawyer who sees the issues presented by my clients and the issues I get inquiries about from potential clients. In that capacity I also read essentially all the new published decisions of the Colorado Supreme Court, the Colorado Court of Appeals and most of the new decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, receive updates in some legal areas from regular services to which I subscribe, and read the Colorado Bar Association and Denver Bar Associations monthly publications on a regular basis.

I sometimes participate in providing answers at Law Stack Exchange and Politics Stack Exchange (where I am a moderator), regularly read How Appealing, the Volokh Conspiracy and at least three law professor's blog (in the sidebar), a blog about the legal profession (About the Law), a blog about legal issues with national security implications (Lawfare, in the sidebar), and economics and politics sites that routinely discuss legal issues.

I also encounter emerging or increasingly relevant legal issues in the general mainstream media (e.g. CNN, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Denver Post), as people ask about or discuss issues on Facebook.

As a result, I have some sense of what areas of law are emerging, more relevant than they have been previously, or are in a state of flux.

This post identifies twenty-five of those legal areas (yes, what constitutes one or multiple legal issues is somewhat arbitrary, one could vary the number simply by being more of a lumper or more of a splitter):

1. Jurisdiction, choice of law, and tax issues pertaining to remote work both interstate and international.

2. Jurisdiction, choice of law, income tax, sales and VAT tax, copyright, patent, rights of publicity, defamation, intellectual property licensing, occupational and professional licensing, business licensing, European and California privacy law, terms of service contracts, online fraud remedies, harassment and cyberstalking, obscenity, human trafficking, and revenge porn considerations that apply to Internet commerce and activity.

3. Privacy laws, in general, including those related to health information, doxing, cancel culture tactics, educational information, and information about Internet activity.

4. Laws about the legality of audio and video recording of conversations and events.

5. Non-competition agreements and non-disclosure agreements.

6. International sanctions laws, war crimes laws, anti-terrorism laws, and extraterritorial jurisdiction.

7. Cryptocurrency issues, especially with regard to income and estate taxation, duties to disclose assets, and money judgment enforcement.

8. Election law (especially election administration law), treason and sedition law, and governmental liability.

9. The propriety of national injunctions, especially in federal public law cases, and issues of forum shopping.

10. Separation of powers issues in the federal government.

11. Dormant commerce clause limitations on legislation.

12. Laws regulated to COVID and public health restrictions.

13. Issues related to abortion law in the U.S.

14. Issues related to gay rights.

15. Gun control.

16. Family law issues in non-traditional families (i.e. in families other than married couples who children, if any, are all traditionally conceived children of both spouses, and other than divorces of such couples), and in non-traditional reproduction means (like surrogacy and IVF).

17. Indian tribe related adoptions, international adoptions, open adoptions, stepparent adoptions, same sex couple adoptions, and means by which a father's parental rights can be terminated to facilitate an adoption.

18. Partition law, i.e. the law of disentangling co-owners of real property outside the context of a divorce.

19. Home owner's association related disputes.

20. Disputes between neighbors regarding property lines, trees, and noise remain surprising relevant and often, surprisingly complex.

21. Issues related to owning real property abroad.

22. Legal issues related to partial marijuana decriminalization.

23. Laws related to black box AI and machine learning decision making, and AI autonomy.

24. Laws related to the civilian and military of drones (especially airborne drones).

25. The legal status of non-citizens in the U.S. both documented and undocumented, of areas outside U.S. states in U.S. jurisdiction, and of Indian country.

23 October 2022

Transgender Identity Is Stable

Transgender teens aren't "confused," nor do they "change their mind" upon reaching adulthood.

Nearly all individuals with gender dysphoria who initiated hormone treatment as adolescents continued that treatment into adulthood, according to this Dutch observational study.Among 720 people who started puberty suppressing hormones prior to the age of 18, 704 (98%) continued to use gender-affirming hormones after turning 18.

Out of the 16 individuals who stopped using prescription gender-affirming hormones by the end of the study at an average age of 19 to 20, nine were assigned male at birth (4% of 220) and seven were assigned female at birth (1% of 500). A total of 12 of these 16 individuals (75%) underwent gonadectomy during this follow-up period.

The summary of the source article and its citation are below:

SummaryBackgroundIn the Netherlands, treatment with puberty suppression is available to transgender adolescents younger than age 18 years. When gender dysphoria persists testosterone or oestradiol can be added as gender-affirming hormones in young people who go on to transition. We investigated the proportion of people who continued gender-affirming hormone treatment at follow-up after having started puberty suppression and gender-affirming hormone treatment in adolescence.MethodsIn this cohort study, we used data from the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender dysphoria (ACOG), which included people who visited the gender identity clinic of the Amsterdam UMC, location Vrije Universiteit Medisch Centrum, Netherlands, for gender dysphoria. People with disorders of sex development were not included in the ACOG. We included people who started medical treatment in adolescence with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) to suppress puberty before the age of 18 years and used GnRHa for a minimum duration of 3 months before addition of gender-affirming hormones. We linked this data to a nationwide prescription registry supplied by Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek) to check for a prescription for gender-affirming hormones at follow-up. The main outcome of this study was a prescription for gender-affirming hormones at the end of data collection (Dec 31, 2018). Data were analysed using Cox regression to identify possible determinants associated with a higher risk of stopping gender-affirming hormone treatment.Findings720 people were included, of whom 220 (31%) were assigned male at birth and 500 (69%) were assigned female at birth. At the start of GnRHa treatment, the median age was 14·1 (IQR 13·0–16·3) years for people assigned male at birth and 16·0 (14·1–16·9) years for people assigned female at birth. Median age at end of data collection was 20·2 (17·9–24·8) years for people assigned male at birth and 19·2 (17·8–22·0) years for those assigned female at birth. 704 (98%) people who had started gender-affirming medical treatment in adolescence continued to use gender-affirming hormones at follow-up. Age at first visit, year of first visit, age and puberty stage at start of GnRHa treatment, age at start of gender-affirming hormone treatment, year of start of gender-affirming hormone treatment, and gonadectomy were not associated with discontinuing gender-affirming hormones.InterpretationMost participants who started gender-affirming hormones in adolescence continued this treatment into adulthood. The continuation of treatment is reassuring considering the worries that people who started treatment in adolescence might discontinue gender-affirming treatment.

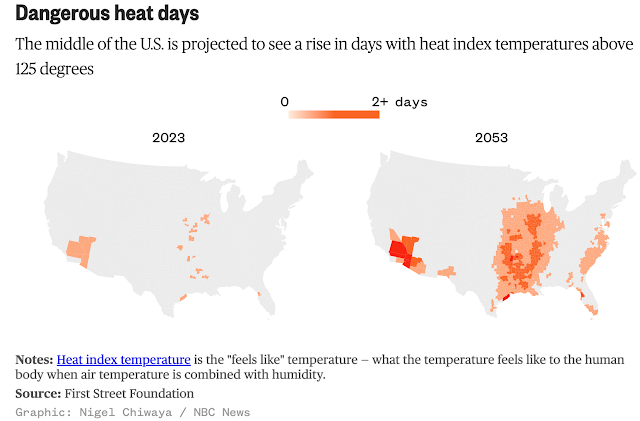

A Generation From Now Lots Of The U.S. Will Get Very Hot

From here.

21 October 2022

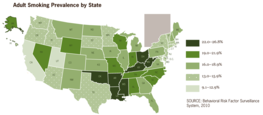

Who Still Smokes In The U.S.?

Tobacco use is significantly more common among men, people in poverty, mentally ill people, people with less education, Native Americans, and people in the South and Appalachia.

It is significantly lower among women, people not in poverty, people with more education, Hispanics and Asian-Americans, Mormons, people over age 65, and people from politically Democratic leaning states.

Smoking Rates Overall and For Men v. Women

In November 2015, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention noted in their report, "The percentage of U.S. adults who smoke cigarettes declined from 20.9 percent in 2005 to 16.8 percent in 2014. Cigarette smoking was significantly lower in 2014 (16.8 percent) than in 2013 (17.8 percent)." The CDC concluded this from data obtained by a survey of Americans.

For instance, current smoking was higher among men at 23.9% than women at 18.1%. This is consistent with other countries.

In 2013, the national smoking average in the United States was 19.6% of the adult population.

As of 2018, a total of 13.7% of U.S. adults (16.7% of men and 13.6% of women) smoke.

In 2005, prevalence of current cigar smoking was 2.2% and current smokeless tobacco use was 2.3%. Prevalence of cigar smoking and use of smokeless tobacco were higher among men (4.3% and 4.5%, respectively) than women (0.3% and 0.2%).

Of U.S. smokers in 2005, 80.8% (or 36.5 million) smoked every day, and 19.2% (or 8.7 million) smoked some days.

Demographic Distinctions

The prevalence of current cigarette smoking also varied substantially across population groups.

Among racial and ethnic groups, Native Americans and Alaska Natives had the highest prevalence at 32.0%, followed by non-Hispanic whites at 21.9%, and non-Hispanic blacks at 21.5%. Hispanics at 16.2%, and Asians at 13.3% had the lowest rates.Smoking prevalence also based on education level, with the highest among adults who had earned a General Educational Development (GED) diploma at 43.2% and those with 9–11 years of education at 32.6%. Prevalence generally decreased with increasing education.The prevalence of current smoking was higher among adults living below the poverty line at 29.9% than among those at or above the poverty line at 20.6%.Persons with mental illness, making up about 20% of the population, consume about 33% of the tobacco used. Persons with serious mental illness die 25 years earlier than average, often from smoking related illnesses.In 2005, the CDC set a 2010 target of 12% for current cigarette smoking prevalence. Certain populations had already surpassed these when it was set. This included Hispanic (11.1%) and Asian (6.1%) women, women with undergraduate (9.6%) or graduate (7.4%) degrees, men with undergraduate (11.9%) or graduate (6.9%) degrees[.]

Smoking percentages by group in the U.S. (2010)

Smoking Rates By Age

Around 4,000 minors start smoking in the US every day.

Adults aged 18–24 years were at 24.4% and 25–44 years were at 24.1% had the highest prevalences.

[In 2005, the smoking rate for] men aged over 65 years [was] (8.9%), and [for] women aged over 65 years [was] (8.3%).

Adult tobacco use by age (2013-2014 survey).

High school student cigarette use (1991–2007). This 20% figure for 2007 is probably high because tobacco use generally has fallen a great deal since 2007.

Regional Variation

The following have some of the lowest percentages of smokers with their states:

Utah, 10.6%, lowest percentage of smokers.

California, 11.7% 2nd lowest.

Hawaii, 14.6%, 3rd lowest.

Connecticut, 16%, 4th lowest.

Massachusetts, 16.4%, 7th lowest.

Vermont, 16.5%, 9th lowest.

There are large regional differences in smoking rates, with Kentucky, West Virginia, Oklahoma and Mississippi topping the list, and Idaho, California and Utah at significantly lower rates.

Smoking prevalence among U.S. adults by state (2010)

Quiting

Among cigarette smokers in 2005, an estimated 42.5% had stopped smoking for at least 1 day during the preceding 12 months because they were trying to quit. Among the estimated 42.5% (or 91.8 million) of people who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetimes (the question the CDC asked to measure if they were ever smokers or not), 50.8% (or 46.5 million) did not smoke currently.

However, researchers said that they are not sure if products like e-cigarettes are in any way helpful to reduce smokers in the country.

From Wikipedia (order rearranged without notation and headings added editorially).

Stray Observation:

One of the biggest divisions within "red state America" is between Mormons and non-Mormons.

Mormons have much less alcohol and tobacco use, marry earlier, have more children, divorce less often, are more engaged with the world outside the United States, are more educated, are more inclined to support public spending on education, and are less rural than other Republican leaning demographics.

While Trump won Mormon strongholds like Utah and Idaho by safe margins, Mormons have been far more ambivalent about Trump than other Republican leaning demographics. In part this reflect their culture roots in New England. Certainly, Mormons and other American conservatives have other points of common ground like opposition to abortion and opposition to gay rights. But Mormons are a cohesive and distinct part of the Republican coalition.

20 October 2022

The Long Ballot

Every voter in the City and County of Denver will vote on 56 to 58 matters in the November 2022 election: 2 federal offices (U.S. Senate and U.S. House), 7-8 partisan state offices, 29 judicial retention elections, 11 state ballot measures, 7 Denver ballot measures, and in some cases one non-partisan RTD director office.

There will be 6 more non-partisan positions for each Denver voters to consider in this spring: the Mayor, the Clerk and Recorder, the City Auditor, two city council members at large, and a district level city council member.

Thankfully, voters are spared non-partisan local school board and RTD district elections in this election cycle.

This ignores runoff elections in the municipal elections and primary elections and caucuses in the partisan races for the midterm elections.

Expecting voters to consider 62-64 different decisions in a six month period is unreasonable and reduces the quality of democratic participation. This should be reformed.

Low Income Workers Are Finally Making Progress In The U.S.

US earnings inequality has not increased in the last decade. This marks the first sustained reversal of rising earnings inequality since 1980. We document this shift across eight data sources using worker surveys, employer-reported data, and administrative data. The reversal is due to a shrinking gap between low-wage and median-wage workers. In contrast, the gap between top and median workers has persisted.

Rising pay for low-wage workers is not mainly due to the changing composition of workers or jobs, minimum wage increases, or workplace-specific sources of inequality. Instead, it is due to broadly rising pay in low-wage occupations, which has particularly benefited workers in tightening labor markets. Rebounding post–Great Recession labor demand at the bottom offset enduring drivers of inequality.

19 October 2022

Judicial Retention Elections In Colorado In 2022

Judicial retention elections apply to state court judges in Colorado and are up down, retain or do not retain elections with a majority need to remove a judge from office. If a judge is not retained, the vacancy is filled by a merit based system with the Governor having a say over which of the three finalists to appoint.

There are eight Colorado Court of Appeals judges facing judicial retention elections in 2022.

In Denver, there are twelve district court judges (the trial court of general jurisdiction) and nine county court judges (the trial court of limited jurisdiction) facing judicial retention elections in 2022.

If you must leave anything on your ballot blank, this is the place to limit the use of your voter research resources because the odds that all 29 judges on the Denver ballot will be retained is in the vicinity of 99.5% this year no matter what you make think about them personally.

I may or may not update this post to discuss the merits of retaining these judges.

A total of 164 judges were eligible for retention in 2022, but only 140 received evaluations and 135 chose to remain on the ballot. Judges may opt to resign or retire prior to their retention for multiple reasons, including the expectation of a negative performance evaluation.

The system was adopted in a 1966 amendment to the Colorado State Constitution and remains a great improvement over the system in place before then.

Colorado State Ballot Issues In 2022

18 October 2022

Criminal Justice System Flaws

No one reasonably acquainted with the facts would conclude that the criminal justice system produce perfect karmic justice, convicting and punishing everyone who commits a crime worth punishing, while wrongfully convicting no one, and violating no one's civil rights. Indeed, no humanly created criminal justice system ever will, and even if could, it would be far too costly a goal to justify the benefit of achieving it.

This doesn't mean that we shouldn't evaluate quantitatively, as best we can, the extent to which the status quo deviates from this ideal, subject, of course to uncertainties like any other scientific measurement. This post considers various metrics of the criminal justice system's flaws that can be considered that are better or less well documented from area to area.

Generally, however, the criminal justice system is well examined academically compared to many other areas of the law, although there are definitely gaps out there too. This post is intended as an overview and reference point for where future inquiry might be necessary and a reminder of areas where what we already know may suggest reforms. It is also intended to help sort of the possible areas of reform with an eye towards assisting in prioritizing the different possible reform areas based upon the magnitude of the problems and the tools available to address them.

Some are frequently voiced as concerns of conservatives (e.g. failure to hold blue collar criminals accountable), others are more frequently voiced as concerns of liberals (e.g. fair treatment of minorities in the criminal justice system and wrongful convictions).

Others aren't on the political radar screen of either major political party even though they are systemic and important (e.g. remedies for people who are charged with crimes, incarcerated prior to trial, have their lives ruined and their fortunes spent on private criminal defense lawyers, and then are acquitted).

Wrongful Convictions

We can, for example, make reasonable estimates of the number of people who are wrongfully convicted.

Wrongful Convictions At Trial

In the State of Colorado, for example, the number of people wrongfully convicted and currently incarcerated following trials and the appellate process is on the order of 200 (about 10% of felonies that go to trial), often facing exceptionally long sentences because these innocent defendants refused to plea bargain and face the long sentences attached even with a plea bargain to lesser charges for very serious offenses.

Wrongful Guilty Pleas

Something on the order of another 200 people (about 1% of felonies resolved by guilty pleas) are wrongfully convicted and currently in prison, but usually facing more lenient than usual sentences for the crimes for which they were originally accused (because the weakness of the guilt-innocence case usually produces favorable plea bargains, and because wrongfully pleading guilty to a lesser charge is a more tolerable choice when the sentence isn't too severe). The percentage of innocent people who plead guilty is lower than the percentage of wrongful convictions at trial, however, because empirically, innocent people are far more likely to go to trial rather than plea guilty than innocent people.

Of course, a large share of people who plead guilty to felonies 40%-60% (perhaps 8,000-12,000) are pleading guilty to significantly lesser charges than the most serious offenses that they actually committed in the criminal episode for which the were charged and are currently in prison, while a fairly modest minority, probably more than 1%, but less than 5% (200-1000 in Colorado) plead guilty to an offense more serious than the most appropriate charge for their conduct.

It is also possible with a bit of effort to identify cases where the risk of wrongful convictions at trial and plea bargains by innocent people are elevated and reduced.

Wrongful Convictions Of Lesser Charges

There are, of course, wrongful convictions at trial and wrongful plea bargains to misdemeanors and lesser charges, and the literature on the accuracy of the criminal justice system in this area is much less carefully studied.

But, given that about half of people incarcerated at any given time are awaiting trial (mostly, but not exclusively, for felonies), that many lesser offenses are almost always sanctioned with fines and/or probation and/or community service, rather than jail time, that minor offenses have lower maximum sentences, and that most minor offenses punishable by incarceration result in post-conviction jail sentences far shorter than the maximum allowed by law, the number of people wrongfully convicted of sub-felony offenses and currently incarcerated for those charges post-conviction at any one time is much smaller.

Also, the collateral consequences of a sub-felony charge apart from the sentence imposed in a particular case are typically far less severe than those in a felony case, so the harm from a wrongful conviction of a such a charge is usually far more modest.

This is despite the fact that the number of sub-felony charges is vastly greater than the number of felony charges brought.

Wrongful Acquittals, Wrongful Pre-Trial Dismissals, And Known Dismissals Of Guilty Defendants

It is also possible to estimate with tolerable uncertainty the number of people who are charge with a crime of which they a guilty who are wrongfully acquitted at trial, which is about 5%-10% of the cases that go to trial each year.

There is far less of a literature on the risk factors that give rise to wrongful acquittals than those that are associated with wrongful convictions, although race and socio-economic status and an ability to afford private defense counsel are often suggested. Likewise, crimes involving strangers and rapes with known offenders who don't deny having had sex with the victim are probably fairly high on the list.

It is harder to estimate the number of cases where people are charged even though the charges are dismissed prior to trial, or arrested but not charged, not because the prosecutor or law enforcement or a victim believes the defendant is guilty but is showing mercy, but because the prosecutor or law enforcement can't comfortably be sure that the prosecutor will prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt at trial. The one exception to this is the subset of cases where a dismissal follows an unfavorable court ruling following a hearing to suppress key evidence that was unlawfully obtained, which involve a guilty person who is spared criminal punishment in the vast majority of such cases, a number that can be reasonably estimated with some precision.

Wrongful Pre-Trial Incarceration And Criminal Charge Defense Costs

One confounding factor, especially for sub-felony offenses and minor felonies, is that a significant share of people who are arrested are incarcerated for some or all of the time prior to their trial, and then either plead guilty to time served which an acquittal at trial can't remedy, or receive a sentence following a conviction which is mostly time served (sometimes following a trial and sometimes following a plea bargain).

People who have been detained prior to trial who plead guilty in exchange for a time served sentence, or a sentence mostly served prior to conviction, make up a particularly large share of wrongful guilty pleas. But, in fairness, even criminal defendants who ultimately plead guilty to lesser offenses and then are sentenced to time served or to only a short remaining sentence (surely at least 80%-90%) are still predominantly guilty as charged, although determining the exact percentage can be challenging.

For example, a great many individuals who are arrested, incarcerated prior to trial and then sentenced to time served or a short additional sentence, are caught red handed by police or on surveillance video while in the act of soliciting prostitution or soliciting a prostitute, selling a small amount of drugs, selling alcohol or tobacco to a minor, trespassing, shoplifting, engaging in porch piracy, committing an aggravated traffic offense, stealing a bicycle, joy riding a stolen vehicle, disturbing the peace, spray painting graffiti, or assaulting someone without a deadly weapon and without causing serious physical injury. The evidence of guilt is unmistakably clear in the lion's share of people arrested and incarcerated in the first place for such minor offenses.

Judges typically have particularly great discretion to impose much longer than typical sentences when sentencing a defendant for minor offenses, so pleading guilty in exchange for time served, cost costs, and often a fine, is often merciful for the offender, cheap for the criminal justice system, and just.

Offenders who are guilty against whom minor charges are voluntarily dismissed by the prosecution without forcing the person arrested to plead guilty, often more affluent defendants with private criminal defense counsel and few or no prior criminal convictions, are similarly situated but even better off because they are spared a conviction on their permanent criminal record. This is particularly valuable for people with few or no prior adult criminal convictions, since an adult criminal record, especially if it is recent, still has some collateral consequences.

Still, people who are detained prior to trial who are acquitted at trial, or for whom the charges are ultimately dismissed prior to trial, in the federal system and all but a tiny number of U.S. states, receive no compensation for the time that they were incarcerated while presumed innocent except in a tiny percentage of cases where flagrant civil rights violations by law enforcement or while incarcerated are proved in a separate civil case. They also almost never receive compensation for the costs they incurred to hire private criminal defense counsel, if any, unless they are corporate executives charged with white collar crimes who are indemnified by their employers.

This is a serious injustice to criminal defendants who are detained for a long time prior to trial who are innocent, and either are acquitted at trial or ultimately have their charges dismissed. The right to a speedy trial mitigates the worst harms in these cases, but it is still incomplete.

Even a week or a month of pre-trial incarceration is often enough to result in the loss of a job, loss of income resulting in evictions or harm to one's credit rating, impairment of an ability to get a new job, negative outcomes in child custody matters, intangible harm to the well-being of one's children, damaged family and romantic relationships, and harm to one's long term reputation from the arrest despite the absence of a conviction.

This burden is overwhelmingly concentrated on wrongfully arrested and charged innocent people who are too poor to post a cash bond to allow them to be released prior to trial. There is also very strong evidence that the lion's share of people incarcerated prior to trial for a failure to post a cash bond (perhaps 80%-90%) pose no serious risk to the public while not incarcerated and awaiting trial.

An upper bound on the number of people who experience wrongful pretrial incarceration, or who incur private criminal defense attorney expenses and are subsequently acquitted or have their charges dismissed is fairly easy to establish with considerable accuracy. One can reduce that figure by a factor of something between 80%-95% or so, to get a reasonable estimate of the number of people who are wrongfully punished based upon mere probable cause when they are actually innocent, prior to trial.

Wrongful Stops and Arrests

The law allows law enforcement to stop someone in a brief "Terry stop" based upon a mere reasonable suspicion that they are engaged in some improper conduct. The harm in any individual case from a wrongful stop of someone who is innocent of any wrongdoing is modest: a few minutes to perhaps ten minutes of time, a certain amount of emotional distress and fear, and perhaps showing up late for one's next appointment. There is no official record of these stops in most cases that don't result in a citation of some kind, so there are also rarely significant collateral consequences from them, although a suspicionless Terry stop can unfairly expose the person stopped to criminal justice consequences for offenses (often minor ones like marijuana possession or underaged drinking) that are usually overlooked. In the individual case, this exercise of discretion towards someone who is actually guilty of a minor offense isn't really unjust, but it is still something of a gray area harm because collectively and over time a pattern of discriminatory Terry stops influences how severely someone is punished relative to their absolute level of criminality compared to other similarly situated people who don't face discriminatory enforcement.

The main harm associated with wrongful Terry stops in a karmic justice sense is that they are typically conducted in a discriminatory manner and efforts to estimate statistically the number of wrongful Terry stops (and wrongful arrests) on racial grounds can provide some quantification of the number of these lesser injustices.

Arrests of innocent people, either with or without probable cause, that don't give rise to pre-trial incarceration (either because the defendant posts bonds, or no charges are ultimately pressed) or to charges resulting in criminal convictions are studied mostly in the context of efforts to quantify racially and ethnically discriminatory law enforcement practices. An upper bound on wrongful arrests is easier to quantify because arrests are generally well documented and can be compared to charging information and conviction information. As noted above, probably 80%-95% of arrests are of people who are obviously guilty and caught red handed, whether there is a formal conviction or not, especially arrests resulting in formal criminal charges being lodged or pre-trial incarceration.

Arrests, because they are longer, may cause someone to have to incur the costs associated with posting bond (which are often 10% of the posted bond if one doesn't have sufficient cash on hand to post it all without a bail bondsman) and possibly private criminal defense costs, neither of which can be recouped in most cases, are more serious. Bail bond fees amount to an unappealable, law enforcement imposed fine on poor people.

Also, the record of an arrest, even if no charges are brought, charges are dismissed, or the person arrested is acquitted at trial, can have significant collateral consequences for future employment, in any pursuit for which there are background checks, and in law enforcement and prosecution attitudes when future criminal charges are considered (even though judges and juries aren't supposed to consider them in trials or in probable cause hearings).

Arrests are very numerous and as with Terry stops, there is strong evidence that they are carried out in a racially and ethnically discriminatory manner, even adjusting for different per capita levels of crime commission that justifies arrests and Terry stops by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and geographic context.

A young black man in a ghetto who is dressed in an anti-authority manner who talks and behaves like a typical man in that demographic out late at night in that neighborhood, who may even have a minor juvenile or adult criminal record or to have received some non-legal system disciplinary punishments at school, is indeed much more likely to have committed a crime than an elderly white woman in an upper middle class suburb who talks and behaves like a typical woman in that demographic in that neighborhood. But his is also vastly more likely to be wrongfully stopped or arrested to a degree disproportionate to the elevated likelihood he has currently committed a crime.

Still, while it can be quantified wrongful stops and arrests because of the much lesser magnitude of the harm are not as much of a problem as their sheer frequency might suggest.

Uncleared Crimes

There is also good data on the number of many kinds of crimes that are committed in which no suspect is ever identified and arrested, the so called "clearance rate".

For a few crimes, like mass shootings or mass stabbings, and rapes where there is DNA evidence, the clearance rate in the long run probably exceeds 90%.

For murders involving organized crime or gangs, the clearance rate tends to be somewhat under 50%.

For other violent crimes, felony property crimes, and more serious misdemeanors, clearance rates tend to be in the 5% to 40% range. The number of truly petty offenses that are never cleared is higher, because few resources are available to address them and many are never formally reported, although insurance claims, crime victimization surveys, and police reports can provide ballpark estimates that can be compared to conviction rates for the crimes in question.

The number of traffic and parking offenses that never results in citations, and the number of safety and regulatory violations not giving rise to actual physical injuries or large scale economic harm to any one individual that are never cited, are basically uncountable. The average driver is technically guilty of speeding many times every day but is typically cited for this less than once a year, and commits scores of other traffic offenses each year but only receive citations for them a few times a lifetime.

Quantifying The Harm Associated With Crimes

The rates at which crimes are not cleared is not the end of the analysis, either. Not all crimes are created equal.

The harm from economic crimes is proportionate to the economic harm done plus some sort of kicker for the preventative measures these crimes make necessary and the sense of victimization and loss of societal trust that they produce even if no physical harm is done. There are lots of good studies quantifying these harms in more and less comprehensive ways.

Traffic offenses in cases where accidents don't result, safety regulation violations, and vice offenses aren't intrinsically wrong (they are not malum per se and are instead malum prohibitum). The costs of non-enforcement of violations of these criminal offenses is a function of the extent to which non-enforcement leads to the harms that these prohibitions are designed to prevent like accidents, STDs, addiction, drug overdoses, other criminal conduct caused by substance abuse, damaged non-commercial romantic relationships, and the creation of a marketplace that encourages people to do degrade themselves.

Violent crimes and certain other non-economic crimes also vary in seriousness, in part, by type of injury and in part by the harm that they do to the social fabric and the economically and socially costly measures that are taken to prevent them. There have been good economic studies attempting to value this harm and they uniformly conform to the conventional wisdom that serious violent crimes are extremely costly in terms of their harm to society as a whole and victims of them in particular.

Serious Criminals Who Are Never Caught

A harder to estimate figure, although there is some literature to allow for crude estimates, is the number of people who commit felonies who are never charged with a crime by the number, type, and seriousness of the crimes.

A reasonable estimate for the number of serial killers and serial rapists (overlapping sets of people) who are never convicted of any serious crime, probably number in scores to low hundreds for the entire nation at any one time, based upon clearance rates in crimes where this is suspected of happening and the frequency with which someone is convicted of serial killings and/or serial rapes only after committing a great many such offenses.

There is fairly good data out there about the average number of burglaries and robberies committed that are not cleared, by any given burglar or robber who is convicted of burglary or robbery, which combined with clearance rates and with studies of the impact of recidivist sentencing for these offenses can be used to make some sort of reasonable estimate of how many serial burglars and robbers are never convicted of serious crimes, although with significant uncertainty.

It is also possible from evidence of convictions to conclude that the lifetime number of serious crimes that a person commits follows a power law whose parameters are possible to reasonably approximate. This data together were clearance rates and confidential survey data on previous uncharged offenses (and non-confidential information on people discovered to have committed many offense when they are first convicted of serious offense) for offenders with different numbers of convictions can be used to make reasonable estimates of the number of people who have never been convicted of a crime who have committed any given number of serious offenses.

The hardest parameter to estimate because it has only weak support in the literature, is the bias which is almost certain to be present to some degree or another, that some criminals are more likely to be caught than others.

This parameter can't be too high for the subset of people who commit crimes who do it as a livelihood, since we can reasonably estimate the share of people who are gainfully employed full time or otherwise engaged in education, training, peaceful retirement, homemaking, and the like.

Quantifying The Effectiveness Of Crime Prevention Measures

One can quantify the effectiveness of various crime prevention measures although doing so is particularly challenging to do well and the approaches to doing so vary greatly.

This can include the effect of different approaches to incarceration and sentencing (including recidivist sentencing and overall incarceration rates), the effects of lead poisoning, abortion legalization, and education, the effects of security cameras and visible law enforcement patrols, the effects of DNA testing, the effects of religious practice and marriage, the effects of youth programs and mental health programs, the effects of wars and weather, and more impacts on crime rates.

Jail and Prison and Parole And Probation Maladministration

One can quantify the extent to which jail and prison conditions, and treatment of people on parole and probation is improper or deficient in preventing harm.

One can look at overuse of solitary confinement which is increasingly well-quantified.

On one hand, one can look at estimates from discipline reports and survey data and prosecutions on crimes by inmates who are incarcerated directed at other inmates, guards, other staff, and visitors, with prison and jail riots at an extreme.

This can also extend to allowing the early release of dangerous inmates who engaged in rampant unpunished misconduct and crimes while incarcerated on one hand, and failing to release model inmates who pose little or no threat to the public on the other when this is allowed.

One can likewise at crimes and misconduct committed by guards and staff against inmates, with indifference to health concerns (especially those related to substance abuse, pregnancy, and mental health issues), indifference to safety from inmate on inmate violence, tolerance for gang activity, sexual abuse of inmates by guards and staff, and other capricious or outrageous conduct.

One can look at undue laxity towards parole and probation violations that can put the public at risk, and a general lack of supervision when needed by understaffed probation and parole departments. One can look for efforts to set ex-cons up for failure or success upon reentry to the general population upon release. And, one can look at abusive and extortionate conduct by parole and probation officers.

Some of this is well-quantified, much of it, especially in the areas of parole and probation supervision abuses and laxity is not.

Quantifying Civil Rights Violations

There are various efforts to quantify civil rights violations. There are estimates of wrongful convictions, wrongful arrests, wrongful stops, and discriminatory exercises of discretion in law enforcement, charging and sentencing and plea bargaining decisions. There is evidence of Brady violations (i.e. failures of prosecutors to disclose exculpatory evidence in a criminal cases). There are include criminal prosecutions, civil actions, settlements, and firings for wrongful law enforcement conduct. There are successful evidence suppression hearings and post-trial collateral attacks on criminal convictions. There is data on when police use deadly force and other kinds of force that can be parsed to identify questionable cases. There is discrimination in employment litigation in the criminal justice system. There are scandals that are reported on in the media demonstrating patterns of misconduct.

There are decent estimates of the percentages of law enforcement officers who have engaged in particular kinds of misconduct, and of law enforcement officers who are witnessed particular kinds of misconduct and failed to report it or take action to prevent it. It isn't perfect or complete, but it is clear that a large percentage of law enforcement officers (far more than a majority), at a minimum tolerate some kinds of legally actionable misconduct that they witness in their peers.