One of the main Russian justifications for the Ukraine War is to provide a land corridor from the rest of Russia to the Crimean Peninsula. But this justification doesn't hold water, because the Crimean Bridge across the Kerch Straight (shown in the red oval below) that connects the shallow Azov Sea and the Black Sea, has been open to road traffic since 2018 and to rail traffic since 2019.

The Kerch Strait . . . connects the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, separating the Kerch Peninsula of Crimea in the west from the Taman Peninsula of Russia's Krasnodar Krai in the east.

The strait is 3.1 kilometres (1.9 mi) to 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) wide and up to 18 metres (59 ft) deep. The most important harbor, the Crimean city of Kerch, gives its name to the strait, formerly known as the Cimmerian Bosporus. It has also been called the Straits of Yenikale after the Yeni-Kale fortress in Kerch.Taman, the most important settlement on the Taman Peninsula side of the strait, sits on Taman Bay, which is separated from the main Kerch Strait by the Chushka Spit to the north and the former Tuzla Spit to the south; the Tuzla Spit is now Tuzla Island, connected to the Taman Peninsula by a 2003 Russian-built 3.8-kilometre-long (2.4 mi) dam, and to mainland Crimea by the Crimean Bridge opened in 2018. A major cargo port is under construction near Taman. . . .

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the government of Russia decided to build a bridge across the Kerch Strait. The 19-kilometre (11.6 mi) Crimean Bridge opened to road traffic in 2018 and the rail section opened in 2019.

The Ukraine War, of course, only began in February of 2022, four years after the road portion of the Crimean Bridge was completed and three years after the rail portion of the Crimean Bridge was completed.

In the 2007 election in Ukraine, much of Eastern Ukraine sided with pro-Russian parties (the blue Party of Regions and the Red Communist Party of Ukraine) over the pro-Western parties (the purple Tymoshenko block and the orange Our Ukraine party) in a closely divided election, but the regions where the second place party was the Communist Party of Ukraine was the most hard core. (The pink Socialist Party of Ukraine didn't win enough support to win seats in parliament and was second place only in areas where the Party of Regions was particularly strong).

Orange Parties (Pro-Western)

Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc 156 seats

Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc 72 seats

Subtotal: 228 seats

Pro-Russian Parties

Party of Regions 175

Communist Party of Ukraine 27 seats

Subtotal: 202 seats

Other Parties

Lytvyn Bloc 20 seats

Total: 450 seats (a majority it 226; a two-thirds majority is 300).

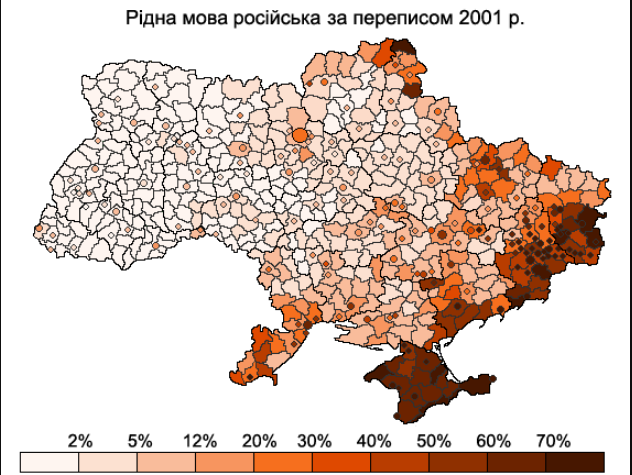

According to a 2004 public opinion poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, the number of people using Russian language in their homes considerably exceeds the number of those who declared Russian as their native language in the census. According to the survey, Russian is used at home by 43–46% of the population of the country (in other words a similar proportion to Ukrainian) and Russophones make a majority of the population in Eastern and Southern regions of Ukraine:

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea — 97% of the population

- Dnipropetrovsk Oblast — 72%

- Donetsk Oblast — 93%

- Luhansk Oblast — 89%

- Zaporizhzhia Oblast — 81%

- Odessa Oblast — 85%

- Kharkiv Oblast — 74%

- Mykolaiv Oblast — 66%

No comments:

Post a Comment