1. The Preference For Capital In The Model Flows Mostly From The Notion That Investment Produces Long Term Benefits While Labor Does Not

What distinguishes these factors and leaves one optimally taxed, the other optimally untaxed? Fundamentally, the difference is that capital accumulates, while labor does not. Judd assumes completely inelastic labor provision, Chamley allows for a labor/leisure trade-off bounded by a fixed number of hours. Each period labor is born anew, while capital stands on the shoulders of its ancestors. This difference is what drives the asymmetry and then the result. Labor is a factor in strictly limited supply, capital is a factor whose quantity can grow indefinitely and which augments labor in production. Under these circumstances, the way to get a big, rich economy — and to maximize the marginal product of labor! — is to encourage the accumulation of capital. Encouraging labor provision directly can’t take you very far, because there is a ceiling. But the sky’s the limit with capital. Further, in Chamley and Judd, nonconsumption automatically implies useful deployment of capital into production.

If these were adequate characterizations of capital and labor, the Chamley-Judd result would be much more plausible than it is. But these are very poor descriptions of the real world phenomena we ordinarily label “capital” and “labor” when we decide how much to tax them.2. Empirically Human And Institutional Capital Matter More Than Physical Capital

[L]abor is not in fact measurable in terms of homogenous hours. What a brain surgeon can do with an hour is very different from what a child laborer can accomplish. Macroeconomically, our collective capacity to produce improves. You might, as Jones does, refer to this incorporeal je ne sais quoi that enhances labor over time as “human capital”, or as labor-augmenting technology. Like physical capital, it seems to accumulate. In empirical fact, “human capital” and its more sociable, incorporeal twin “institutional capital” seem to be much more important predictors of the growth path of an economy than physical capital. Europe and Japan bounce back quickly after war devastates their infrastructure. But imagine that a Rapture clears the Earth and pre-agrarian nomads take possession of perfect gleaming factories. I think you will agree that production does not recover so fast. Human and institutional capital dominate physical capital. [3]

[3] It was Garret Jones himself who offered the single most insightful economics tweet of all time, on precisely this topic:

Workers mostly build organizational capital, not final output. This explains high productivity per ‘worker’ during recessions.

Like physical capital, and unlike hours of the day, the collective stock of human capital grows over time, without obvious bound. Yet, at least under existing arrangements, we have no means of distinguishing between “returns to human capital” and “wages”. “Capital taxation”, in conventional use, refers to levies on capital gains, dividends, and interest. As a political matter, results like Chamley-Judd are often used to support setting these to zero. But eliminating conventional capital taxes shifts the cost of government to wages, which include returns to human capital. If human capital accumulation is as or more important than other forms of capital accumulation, and if the quality of effort that people devote to building human capital is wage-sensitive, then taxing wages in preference to financial capital may be quite perverse. . . . Fundamentally, Chamley-Judd logic suggests that we should tax least the factor most capable of expanding to engender economic growth. You don’t have to be a new-age nut to believe that human and institutional development, which yield return in the form of wages, may well be that factor. It is perfectly possible, under this logic, that the roles of capital and labor are reversed, that the optimal tax on labor should be zero or even negative, because returns to physical and financial capital are so enhanced by human talent that even capitalists are better off paying a tax to cajole it. . . .3. Financial Savings And What The Model Calls Investment Are Not The Same Things

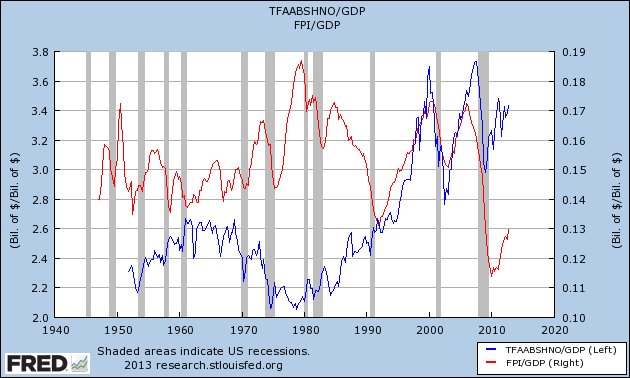

Empirically, the relationship between the outstanding stock of financial claims and anything recognizable as productive capital is very weak. [4]

[4] Within the sphere of financial claims, the relationship is sometimes stronger: there may be a relationship between, say, the aggregate balance sheet size of the telecoms industry and fixed investment in telecoms. But the aggregate quantity of financial claims as a whole (restricted to those held by households to avoid double-counting of “pass-through” holdings) has no stable relationship to the quantity of measurable investment in the economy:

TFAABSHNO → “Total Financial Assets – Assets – Balance Sheet of Households and Nonprofit Organizations”, “FPI” → Fixed Private Investment; I should probably have included gross foreign holdings in the financial assets measure, but the series I’d need, though available in the flow of funds, seems not to be published on FRED. (It’d be Table L.106, “Rest of the World”, “Total financial assets”, Line 1 if anyone is more motivated than I am to find the full series and add it to household financial assets.) [End Footnote]

In the models, foregone consumption and productive investment are inseparable. In the real world, purchasing a financial asset (or holding money!) does imply that some agent forgoes consumption. But it does not imply that the foregone consumption will be invested. The consumption an agent forgoes may be consumed by others. It may be wasted. . . . In real life, there are a lot of those revaluations, and no measure of observable capital corresponds with a cumulation of financial savings. So, if we want to take Chamley-Judd reasoning seriously, we oughtn’t set tax rates capital gains, dividends, or interest to zero. Instead, we should ensure that real investment activity by firms is tax advantaged. There is no Chamley-Judd case for not taxing the interest on consumer loans or government bonds that finance transfers. There may be a case for policies like accelerated depreciation of fixed capital or even tax credits for education expenses. [5] But given the weak relationship between financial assets and real investment, eliminating conventional “capital taxes” just subsidizes the products of the financial sector. It offers a windfall to financiers and their best customers, but creates no foreseeable “piece of a bigger-pie” benefit for the people to whom the tax burden is shifted.

[5] Interestingly, Andrew Abel points out that, under conventional Chamley-Judd assumptions, not worrying at all about human capital or the imperfections of finance, optimal tax policy may be to tax only capital, but to permit the ultimate in accelerated depreciation, immediate expensing of capital goods.4. Aggregate Saving Rates Are Empiricallly Insensitive To Returns

The force that drives the Chamley-Judd conclusion is the long-term elasticity of capital provision to interest rates. The intuition is that capitalists make a decision about whether to forego consumption and contribute to growth or whether to consume today based on a comparison between available returns and their time preference. Lower capital taxes keep returns higher and make contributing capital “worth the wait” over a longer arc of the production function, leading to a higher steady state.

Unfortunately, this sort of calculation does not seem to describe economy-wide savings behavior very well. Aggregate purchases of financial assets seem to be insensitive to returns. In the US, yields on debt, risk-free, corporate, and individual, have been falling since the 1980s, while the stock of financial assets held by households (as a share of GDP) has grown inexorably. (Total equity returns were high only in the 1990s; financial holdings grew about as fast during the low-debt-yield, low-return pre-crisis 2000s as they did in the 1990s, see the graph below.) Unless you posit a peculiarly declining time preference, the core implication about aggregate savings behavior in any Ramsey model seems quite false. We need other stories. I have some! Perhaps consumption is approximately satiable, and the fraction of income saved is just a residual, the difference between income and the satiation level. Perhaps wealthier households save, not to endow future consumption, but because they are in a competitive race with other households for insurance or status that derive from financial holdings. Perhaps for the US, aggregate saving is largely a residual of other countries’ return-insensitive economic policy (Asian mercantilism, petrodollar recycling, etc.). In any of these cases, we’d expect gross financial saving not to be especially sensitive to investment returns. Now human capital formation may be less wage-sensitive than we’d guess too. Maybe we become brilliant more because of expectations and support provided by the people and institutions that surround us than because of the extra money we anticipate. But all these uncertainties undermine the Ramsey/Chamley/Judd edifice, rather than suggesting a zero capital tax.5. There Are Diminishing Returns To Most Kinds Of Investment

Another point is that the argument for zero taxation of gains from capital falls apart when there are diminishing returns from new capital investments.

With modestly decreasing returns to scale, the optimal tax rate is positive; with constant returns to scale the optimal tax rate is zero; with modestly increasing returns to scale, the optimal tax rate is negative.The notion that investments can have diminishing returns flows naturally from the assumption that investors rationally invest in the investments with the greatest returns first, and only consider less beneficial investments when the better ones have been made already.

6. Government Spending Has Productivity Enhancing Value And Taxing Poor People Is An Inefficient Way To Generate Government Revenue

None of these critiques address the fact that government spending has economic value, and that we primarily tax people to generate revenues, rather than primarily to tweak economic incentives. A material share of government spending constitutes investments that increase the nation's productive capacity: roads, medical research, the Internet, dispute resolution mechanism for businesses, and schools, for example, are all basically the product direct government investments.

Optimally, the marginal dollar of public sector spending and the marginal dollar of private sector spending have the same marginal utility. Undertaxation produces suboptimal results. But, the only way for taxes to generate revenue is for them to tax people who have an ability to pay, which generally means people who have physical or human or institutional capital. Taxing poor people is not a good strategy for generating adequate government revenue.

7. The Assumption That Higher Productivity Means Workers Are Rewarded Is Flawed

The model argues that worker pay is tied to how productive they are.

It is wonderful for Jones to remind his students that, especially in a context of full employment, “capital helps workers”. Stories of what a worker can accomplish with a bulldozer versus a shovel are important and on-point. Students should inquire into the process by which in some times and places construction workers get bulldozers and live well, while in other times and places they work much harder with shovels yet barely subsist.The evidence of the last few decades, however, is that the lion's share of GDP growth has been captured by capitalists without providing a benefit to workers. The historic trend of shared benefits from GDP growth seen in the highly unioned 1950s and 1960s is gone. It is not in the interest of workers to tax themselves in order to allow someone else to get rich.

No comments:

Post a Comment