More personality traits and mental health conditions have significant genetic components (statistically) but almost no variability attributable to shared environment. The main exceptions are IQ (32%) and anti-social behavior (31%) in children, which show significant shared environment effects, although shared environment effects are much less pronounced as people get older (4-5%).

Thus, parents can influence childhood intelligence and rates of anti-social behavior, but not personality or the manifestation of mental health conditions. Parental influence declines in adults over time, however, as people gravitate in the direction of their genetics.

Shared Versus Nonshared Environmental Influences

Whereas the dominant theoretical and empirical traditions within developmental psychology have emphasized the influence of shared rather than nonshared environmental factors, behavioral genetic research is consistent in showing that environmental influences on most psychological traits are of the nonshared rather than the shared variety (Plomin & Daniels 1987).

For personality characteristics, the MZT correlation has consistently exceeded the corresponding DZT correlation by more than a factor of two. This observation, first noted by Loehlin & Nichols (1976) but replicated in diverse cultures with thousands of twin pairs (Loehlin 1992), implies a shared environmental component of zero. Alternatively, the consistently high ratio of MZT to DZT correlation could reflect genetic nonadditivity, or greater environmental sharing among MZT as compared with DZT twins. It is thus significant that findings from studies of reared together twins have been replicated using alternative research designs. For example, MZTs are not markedly more similar in personality than MZAs. In the four published studies comparing the similarity of MZA and MZT twins on the two most fundamental dimensions of personality, extraversion and neuroticism, the weighted average MZA correlation is .39 for both factors (summarized by Loehlin 1992). The comparable MZT averages are .56 for extraversion and .46 for neuroticism. Secondly, the correlation for nonbiologically related but reared together sibling pairs (i.e. adoptive siblings) provides a direct estimate of the effect of common rearing; in three adoption studies of adults (summarized by Loehlin 1992), the weighted average adoptive sibling correlation was −.07 for extraversion and .09 for neuroticism, while in a single adoption study of adolescents, the adoptive sibling correlation was −.04 for a measure of extraversion and .00 for a measure of neuroticism (McGue et al 1996).

The minimal effect of common rearing appears to hold not only for personality factors but also for most major forms of psychopathology. Adoption studies of, for example, schizophrenia (Gottesman 1991) and alcoholism (McGue 1995) indicate that risk to the biological offspring of an affected parent is independent of whether the offspring is reared by the affected parent, while twin studies of most behavioral disorders reveal a greater than 2:1 ratio of MZT to DZT concordance (see above).

There are, however, two noteworthy exceptions to the general finding of little shared environmental influence on behavioral characteristics: cognitive ability and juvenile delinquency. From a compilation of familial IQ correlations (Bouchard & McGue 1981), the following observations all support the existence of substantial shared environmental influences on general cognitive ability: (a) the average MZT IQ correlation (.86) is less than double the corresponding average DZT correlation (.60); (b) the average MZA correlation (.72) is moderately lower than the average MZT correlation; and (c) the average adoptive sibling correlation (.32) is substantial. Taken together, these observations suggest that from 20% to 30% of the variance in IQ is associated with shared environmental effects (Chipuer et al 1990).

The overwhelming majority of the twin and adoptive sibling correlations for IQ are based on preadult samples, for which the effect of shared environmental factors may be maximal. As noted above, when twin IQ correlations are categorized according to the age of the twin sample (McGue et al 1993), the ratio of MZT to DZT correlation is found to increase with age such that in adult samples the average MZT correlation (.83) exceeds the average DZT correlation (.39) by more than a factor of two, suggesting no shared environmental influence at this life stage. Moreover, the average adoptive sibling IQ correlation equals .32 in studies of children or adolescents (summarized in Bouchard 1997a), but, as already noted, only .04 in studies of adults. The adoptive sibling correlation decreased with age in each of the three of these studies that involved longitudinal assessment of IQ. Shared environmental influences on IQ, although substantial in childhood, appear to decrease markedly in adulthood.

The pooled concordance rates for male juvenile delinquency are high and similar for MZT (91%) and DZT (73%), suggesting a substantial influence of shared environmental factors (Gottesman & Goldsmith 1994). Similarly, twin correlations for delinquency assessed quantitatively (e.g. as number of delinquent acts) rather than categorically find evidence for strong shared environmental effects (Rowe 1994, Silberg et al 1996). Like IQ, the influence of shared environmental factors on adolescent antisocial behavior may diminish in adulthood. In a sample of more than 3000 US veteran twin pairs, Lyons and colleagues (1995) reported that the heritability of antisocial behavior increased from .07 in adolescence to .43 in adulthood, while the proportion of variance associated with shared environmental effects decreased from .31 in adolescence to .05 in adulthood. The matter is not fully resolved, however, as a subsequent investigation of more than 2500 Australian twins (Slutske et al 14 McGUE & BOUCHARD 1997) reported significant heritability (.71) and no shared environmental effect for retrospectively assessed adolescent conduct disorder.

From Matt McGue and Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr , "Genetics And Environmental Influences On Human Behavior Differences", 21 Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1–24 (1998) (emphasis added).

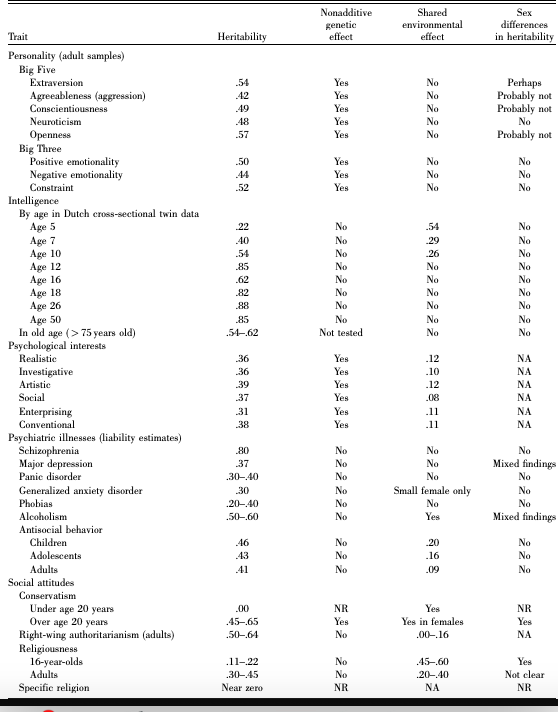

A 2004 follow up review of the data by Bouchard is a major reference point for the issue. It results were as follows:

A 2004 follow up review of the data by Bouchard is a major reference point for the issue. It results were as follows:

This shows modest (ca. 8-12%) impacts on psychological interests (consistent also with the study below), a shared environmental impact on alcoholism, the same age dependent impact on IQ and anti-social behavior (9% of which endures to adulthood), as well as an age dependent shared environmental impact on religiousness.

It found a shared environmental impact on conservatism (with no genetic impact in children, but a great deal in adults) and some weak shared environmental impact on right wing authoritarianism in adults (which also shows strong genetic impact in adults).

Gender effects are small and uncertain except for a definite presence in religiousness, conservatism, and possibly extraversion, major depression and alcoholism.

It found a shared environmental impact on conservatism (with no genetic impact in children, but a great deal in adults) and some weak shared environmental impact on right wing authoritarianism in adults (which also shows strong genetic impact in adults).

Gender effects are small and uncertain except for a definite presence in religiousness, conservatism, and possibly extraversion, major depression and alcoholism.

A 2006 study by Michael F. Streger, et al., similarly examined 24 other personality traits and found possible shared environment influences in just two of them, and they were weak.

[C]orrelations among MZ twins are generally large, with some exceptions, whereas correlations among DZ twins are generally small to medium. These results would lead us to expect substantial genetic effects, and this is what we observe when we fit ACE models. Two scales exhibited weak evidence of shared environmental effects: open-mindedness, c^2 =.10 (95% confidence interval [CI]: .00, .49), and love of learning, c^2 =.18 (95% CI: .00, .56). Because there was so little evidence of shared environmental influences, we tested AE models for each of the scales. . . . the estimates of additive genetic factors (A), ranging between .14 (14% genetic influence) and .59 (59%), with a median estimate of .42 (42%), indicate a level of genetic influence similar to that observed for other psychological traits (Bouchard, 2004). Lower bounds of 95% confidence intervals were greater than zero for 21 character strengths. There is also substantial evidence of non-shared environmental influence (E) on variability in character strengths, with estimates ranging between .41 (41%) and .86 (86%; median= .58, or 58%).

Both of the shared environmental effects seen are for traits that could fairly be characterized as psychological interests, consistent with prior research.