Well Prepared For Academia, Less Well For Law

Until I graduated from law school (a year and a half early, because I finished college in three years and law school in two and a half years), I lived my entire life ensconced in academia, and continued to have close ties to it for another five years or so after finish law school.

This was great preparation for being a professor, and I was an associate professor in the graduate degree program at the "for profit" College for Financial Planning (a sister college of the University of Phoenix), for fifteen months and would have happily continued doing so indefinitely, before I was laid off on a last hired, first fired basis, because the College wasn't meeting its profit targets (I did have a low volume moonlighting solo practice of law in that time period as well).

I've published three subject matter articles in state bar magazines and presented two papers at academic conferences for law professors.

I taught thirty-three continuing education course for lawyers and paralegals in the last twenty years on a variety of subjects. Some of those classes have been as short as an hour, but many have been all day affairs including one recent class where I prepared materials to support five hours straight of lectures which I delivered, in part, because one of my two co-presenters had to drop out of teaching the all day class.

I read perhaps a dozen or two academic journal articles a week (although, to be honest, I only carefully read one to three of them cover to cover in detail and really analyze them)

I discuss what I read and answer questions from people at my two blogs, and sometimes more summarily, in a Facebook post, or in online discussion forums like Stack Exchange, Physics Forums, or other people's blogs.

I have the third highest reputation out of more than thirty-three thousand contributors at Law Stack Exchange (which is probably the leading and most authoritative English language legal discussion forum open to the general public in the world) and the ninth highest reputation out of more than thirty-four thousand contributors at Politics Stack Exchange. I am in the top 6% by reputation at Physics Stack Exchange (something usually reserved for physics graduate students, high school physics teachers, and physics professors), and I am a well regarded "Gold" contributor to the Physics Forums.

I have also shared my studies by making about fifteen hundred edits to dozens of Wikipedia articles, mostly about law, physics, and historical linguistics, but also about a variety of other subjects. I am a principal or original author of several Wikipedia articles, including, for example, an article in the area of angelology, some popular culture entries, some biographical entries, a few legal terms and concepts, and a few physics concepts. I have also written many articles at the left leaning dKosopedia including most of their coverage of military, water, and agricultural issues.

My academic training and hands on college experiences were also good preparation for the work that I did for a year and a half as a part-time professional journalist covering a law and politics beat, writing a couple of articles or so every week for an online magazine. I had been a radio news reporter in college, and after moving to Denver, I had been a regular guest contributor to a call-in talk radio show about business and finance for a couple of years.

My writings have been cited in a variety of published academic journal articles on subject including taxation, law, politics, and linguistics, and are included in the Lexus-Nexus database. One of my articles on military affairs was made part of the course materials at a class at the British military's war college. I've even won a Westword "Best of Denver" award for my blog writing, where I have made more than ten thousand posts since 2005.

But this background and these experiences provided me with none of social capital or context I would have to develop for the work I've in a mixed transactional and civil litigation law practice, working mostly with closely held businesses and affluent individuals clients, that I've had for what will be, as of this summer, the past twenty-seven years. This, I had to learn as I went, and most of my peers were ahead of me in this regard when I was in law school.

How I Got Here

My father was a professor. I grew up in a small college town (Oxford, Ohio). My mother, when she returned to the workforce after my brother and I were old enough, was a university administrator and earned a PhD while working in that capacity (she earned a master's degree before I was born). While I was in junior high school, I read many of my mother's graduate school textbooks in educational leadership. I read articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education from the time I was in junior high school until I left for college and also when I was home from college on breaks. I took half my classes in my senior year at the local university rather than my high school. A large share of my peers growing up were likewise the children of university employees.

After I left the college town where I grew up, I spent my undergraduate years in another small college town (Oberlin, Ohio), and then went to law school (I started classes less than twenty-four hours after I graduated from Oberlin) in a big college town (Ann Arbor, Michigan).

Growing up, my family had a small law firm lawyer who lived just down the street, who assisted my parents in estate planning, probate, and real estate matters, and represented my brother in a personal injury case after he was hit by a car while crossing the street about a hundred feet away from our lawyer's home. But I had never interacted with him professionally, and really had no idea what the daily life of a real lawyer was like.

At my first summer job in law school, I was a research assistant for a government commission that one of my law professors served upon. At my next summer job, I was a summer law clerk in a medium sized law firm, but that peon level attorney job mostly involved writing legal research memorandums.

After graduating from my top ten law school (cum laude in the top quarter of my class with several awards and experience as a senior editor on one of the secondary law reviews at our law school), I did document review as a law clerk while I was studying for the bar exam for an attorney in downtown Buffalo, New York, mostly on the Love Canal superfund site insurance coverage litigation. Litigation related to Love Canal started in earnest in 1978 and was still going strong seventeen years later in 1995 when I was working on it, trying to get useful information from discovery materials kept in 1980s era litigation support databases.

After passing the bar exam (using only about half the allocated time to complete it and then leaving early after each testing session, with a multi-state bar exam score in the top 1% of law school graduates and a perfect professional ethics exam score), I worked two more weeks for that attorney as an actual lawyer doing essentially the same week and got myself admitted to the federal court bar as well as the New York State bar to which I'd already been admitted, but then was laid off when he lost what had been his dominant client for the past decade (85% of his billings) in a corporate merger of his client with another whose existing legal team won the work.

At that point, I spent about nine months in solo practice in Buffalo, New York, It wasn't terribly profitable because I didn't have a big volume of work, but the work that I did do was quite sophisticated. I handled the sale of a small business and its related real estate. I did the transactional legal work for a multi-million dollar floor plan financing for a car dealership for a private investor. I handled a couple of copyright matters. I dealt with an international custody dispute. I wrote some wills and trusts. I absolutely learned many things about both substantive law and the practice of law in the process, but I didn't have any mentors or attorney peers, and I had no context for the world of law and business from my life experience. Instead, I relied more or less entirely on my law school and bar exam studies and self-study. I also looked for jobs as a lawyer working for others.

But even then, I was still closely connected to academia, because my wife was in graduate school at SUNY-Buffalo studying for her master's degree. We discussed the classes she was taking and her experiences teaching sections of women's studies classes. I provided administrative support (like transcribing interviews, since I was a good typist, and proofreading) in connection with her master's thesis (which incidentally has now been cited by published academic journal articles numerous times).

Eventually, now twenty-five years old and married, I ended up in a medium sized law firm (eleven or twelve lawyers) in Grand Junction, Colorado that was more than a hundred years old and was one of the two largest law firms in Western Colorado.

Even then, I was close to academia. My wife moved to join me as soon as she finished her master's degree, spent a year as an English composition instructor at Mesa State College (it has subsequently changed its name), and the balance of our time there as a college administrator in their admissions office, also handling issues for foreign exchange students studying there from abroad.

I would end up working at this Grand Junction law for three years, before moving to new job where I was hired laterally by a small law firm in Denver. We moved because we were about to have children (our actual move took place about two months before our first child was born), and some racist incidents at the time there made it clear that Grand Junction, Colorado was not a safe or nurturing place to raise a multi-racial family.

But I learned valuable lessons there. It was the most well established and most well run law firm I have ever worked for as a lawyer, before or after that job. It had good systems in place, appropriate staffing levels filled with employees who were more competent than average and had been working as a team for a long time, and a savvy and seasoned group of attorneys who worked well together.

The mentoring that I received there from the partners in the law firm is where I first really learned about the aspects of law that aren't taught in law school and aren't easily learned from books, like conducting negotiations, taking depositions, preparing for trials, conducting client meetings, coordinating with other lawyers and staff, and preparing adequate time entries. I also learned about the way business and financial and estate planning deals are customarily done, and the larger business and financial and social context involved in being a lawyer.

About Negotiations

One of the first, nearly iron-clad laws of negotiations that all other lawyers seemed to already know and understand, was "don't negotiate against yourself."

In other words, in a negotiation, once you have made an offer, you don't make another less favorable offer while you are waiting for the other party or parties in the negotiation to accept your offer or make a counteroffer. If they reject your offer without making a counteroffer, then a deal doesn't happen at all, in a transactional matter, and you try to win the case with motion practice or by going to trial, in litigation.

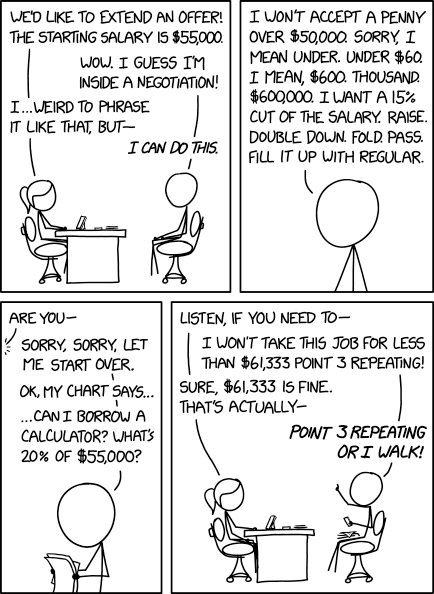

The most recent comic from xkcd, entitled "Salary Negotiation" illustrates nicely, although to the point of absurdity, why this is a good idea:

Mouseover text: "We can do 0.33 or 0.34 but our payroll software doesn't allow us to--" "NO DEAL."

Salary negotiation itself, is quite a salient issue right now in our family.

My son recently negotiated his summer job employment terms, my daughter just negotiated the terms of her second full time, permanent "real job" (with a 40% pay increase from her current position), her significant other just secured a raise at his first post-college "real job" and support for a professional development program that will put him on track for further advancement in his career, and I negotiated an 80% increase in the rate I am paid when working in an "Of Counsel" capacity two or three years ago after it had been stagnant for seven or eight years.

My wife left the work force when the pandemic hit because her industry of doing promotional modeling and serving as a brand ambassador basically ceased to exist overnight, and our household suddenly doubled in size, with the extra stresses of having everyone working and studying from home and basic grocery supplies becoming challenging to get for a while. But prior to that, working as an independent contractor, she would engage in a dozen or so new job negotiations every year.

No comments:

Post a Comment