Overview

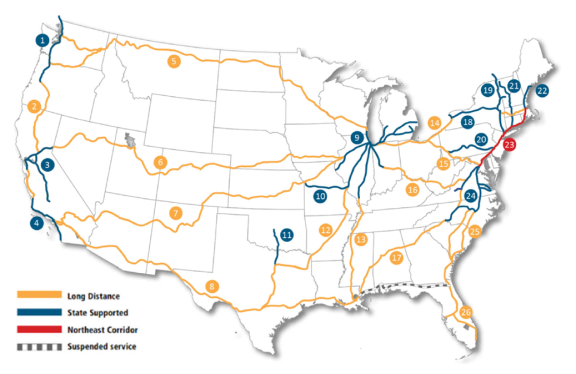

Outside the Northeast Corridor, intercity passenger rail service is limited to Amtrak, which provides infrequent (often once or twice a day) service at speeds averaging 40 miles per hour or less, at costs significantly greater than intercity bus service by far less heavily subsidized Greyhound with no meaningful advantage in speed relative to intercity bus service.

But significant progress in U.S. passenger rail service will arrive over the next six or seven years.

There is a medium speed (79 mph) route in Florida from Miami to West Palm Beach that closed in March 2020 due to COVID and will reopen in late 2021. It will be extended to Boca Raton by mid-2022 and to Orlando by the end of 2022, with plans in place to further expand it from Orland to Tampa with no fixed timeline in place.

A high speed (200 mph) route from Las Vegas to Southern California starts construction in April with completion of a first phase planned for late 2024, and an extension bringing it closer to existing slow passenger rail lines into Los Angeles planned as a second phase.

A high speed (200 mph plus) route from Dallas to Houston starts construction in June with completion planned for 2027.

California and Nevada

The red line low speed passenger rail lines currently exist; the blue line begins construction in April; the yellow line is in a design-concept phase only.

Construction on an $8 billion 170 mile bona fide high speed rail line from Las Vegas to Victorville on the outer fringe of the Los Angeles metro area, more or less along I-15 will probably begin in April of this year (a year behind a scheduled that was delayed due to COVID-19 related interruptions of a bond offering to pay for it).

The company behind the plan, Brightline West, is also attempting to expand this first phase of the project to Rancho Cucamonga and Palmdale, California, where riders could then link to downtown Los Angeles via Metrolink.

Realistically, a planned 2023 completion date for the portion of the route to Victorville will be pushed back to the end of 2024, but this is still less than four year away., will be the first truly high speed rail line in the United States. The new high speed trains will make the 170 mile trip in 85 minutes at an average speed of 200 miles per hour.

After missing its planned 2020 construction start date, the company behind the high-speed rail project between Las Vegas and Southern California is hopeful work could begin this year. Brightline West plans to begin construction on the approximately 170-mile rail line between Southern Nevada and Victorville, California, as early as the spring, according to a project status update filed Jan. 4 with the Nevada High-Speed Rail Authority. “The purpose of this letter is to provide a status update on the project, which is on target to commence construction in early Q2 2021,” Sarah Watterson, president of Brightline West, said in the letter. . . .

Late last year, Brightline postponed a $2.4 billion bond sale that would have generated the financing for the initial portion of tracks and stations of the long-talked about $8 billion project. The company blamed the delay on market instability due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. . . . After Brightline canceled the bond sale, both California and Nevada repurposed the private activity bonds approved for the project — $200 million in Nevada and $600 million in California — to go toward affordable housing in each state. . . . stakeholders have expressed support for a new allocation of private activity bonds in 2021. . . . Terry Reynolds, director of the Nevada Department of Business and Industry, said there have been no discussions between the state and Brightline regarding the timing of reissuing private activity bonds. Mark DeSio, spokesman for California Treasurer Fiona Ma’s office, also said no talks have been had with Brightline this year regarding the potential reallocation of bonds. . . . “We would most likely be looking at a time frame around the third quarter of 2021,”[Reynolds] said.

Brightline spokesman Ben Porritt said the company continues to make progress on expanding its plans, looking to connect into Los Angeles County and is keeping officials in both states updated on developments. . . .In addition to the planned Las Vegas to Victorville track, Brightline is also working on potential links to Rancho Cucamonga and Palmdale, California, where riders could then link to downtown Los Angeles via Metrolink.

From the Las Vegas Review-Journal (January 13, 2021).

Florida

Sister company Brightline Florida has building a "medium speed" rail line, faster the Amtrak service in most of the U.S. and comparable to the service provided by Acela service in the Northeast Corridor, along the Atlantic coast of Florida starting at Miami to Orlando and then on from there to Tampa in a second phase.

Service to three stations with a peak speed of 79 miles per hour on the first 72 mile portion of the route from Miami to West Palm Beach began in 2018 but was halted in March 2020 due to COVID. Service on this portion of the line is scheduled to resume in late 2021. As noted in a previous post at this blog:

An expansion to Orlando, a three hour, 240 mile trip from Miami with peak speeds of 125 miles per hour to the North of West Palm Beach, due to completed in 2022. This compares to highway travel times of 3 hours 30 minutes to 3 hours 45 minutes between the same destinations.

The anticipated Miami to West Palm Beach portion cost about $1.1 billion, and the West Palm Beach to Orlando route is anticipated to cost is $2.4 billion.

Brightline Florida raised $950 million in a December 2020 tax exempt bond offering to financing continuing work on the West Palm Beach to Orlando leg of the project. The Boca Raton station is scheduled to open in mid-2022. the Orlando station is still on track to be completed in late 2022, less than two years from now.

Texas

Regulatory authorization is in place and $20 billion of construction by the Texas Central Railroad company will begin by June of this year on a high speed rail line from Dallas to Houston that would make that trip in 90 minutes at speeds of more than 200 miles per hour. By I-45, the roughly 240 mile trip takes about three and a half hours. The sites of the Dallas, Brazos Valley and Houston stations and about 40% of the land for the track routes has been acquired.

This Texas high speed rail project is scheduled to be finished in 2027.

Amtrak Service In The Northeast Corridor

About 38% of Amtrak service, as measured by passenger trips, are in the Northeast Corridor.

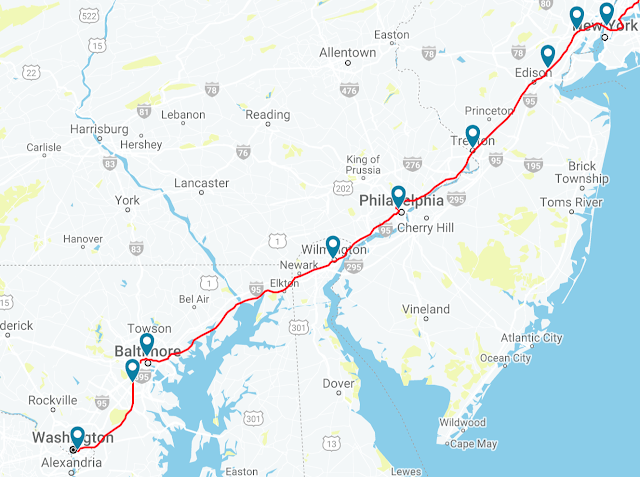

The Amtrak owned and operated Acela medium speed passenger rail line averages 82 miles per hour from D.C. to New York City, and 66 miles per hour from New York City to Boston (the full trip takes 6 hours and 40 minutes give or take about ten minutes).

Acela service captures 75% of the air/train commuters between New York City and Washington D.C., and 54% of the combined air and train travel from Boston to New York City (but only 6% of all intercity trips in the region).

New train cars with more passenger capacity and the ability to handle upgraded rail lines and to travel slightly faster than existing train cars on 457 mile medium speed Acela line from D.C. to Boston will start to enter service this year and will fully replace the existing train cars by 2022.

For example, if you want to go from Washington, DC, to Pittsburgh 250 miles away, you are looking at either a four-hour car trip or a seven-hour-and-43-minute Amtrak ride [less than 33 miles per hour]. What's more, there's only one train per day that makes the trip, departing DC a bit after four and arriving in Pittsburgh a bit before midnight. Of course, with the train so slow that there's no practical case for using it, there's little point in scheduling more trips. Megabus offers a slightly faster journey with two trips per day and charges $10 to $15, while Amtrak's fares start at $50.

Similarly, a trip from Denver to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, which is 157 miles and takes 2 hours and 33 minutes via I-70 by car (averaging 61 miles per hour), takes 5 hours and 41 minute via Amtrak (averaging 28 miles per hour), with only one trip available per day leaving at 8:05 a.m.

Average Amtrak service speeds outside the Northeast Corridor are comparable to intercity bus service (which are slowed by many stops en route) and are equally likely to be faster than slower.

Cost

In order to provide this inferior service, in addition to fares that average 35.6 cents per mile (including the Northeast Corridor) it receives combined federal, state and local subsidies of about 26.4 cents per mile for the system as a whole (including the Northeast Corridor which breaks even on operating costs although not in total costs) for a total cost of 62 cents per passenger mile. In all, Amtrak receives about $1.5 billion per year from the federal government and about $0.2 billion per year from state and local government. Amtrak's long haul routes are especially unprofitable.

Amtrak requires significant operating subsidies outside the Northeast Corridor. In a sample of 18 trips considered in one study:

For the remaining eighteen trips the average government (state and federal) subsidies to Amtrak range from $21.93/passenger to $289.56/passenger. By comparison, for the twenty trips analyzed the total indirect capital subsidies (Highway Trust Fund outlays) provided to support surface transportation range from $0.09/passenger to $0.74/passenger.

On selected long routes with low ridership (which are maintained, in part, for political purposes so that it can tout to Congress that it serves 46 U.S. states), the cost of a commercial airline ticket between the same destinations in many cases, with a flight time that is 10% of the Amtrak travel time.

By comparison, air travel has a combined cost of about 15 cents per passenger mile (including about 1.25 cents per passenger mile of government subsidy), the combined cost of travel by car is about 24 cents per passenger mile (including an about 0.8 cent per passenger mile of government subsidy), and intracity public transit has a combined cost of about $1.21 per passenger mile made up of about 29 cents of passenger fares and 92 cents of government subsidies per passenger mile.

More background is available in a January 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service report which among other things recounts the fact that 2020, due to COVID, was a horrible year for Amtrak.

Some of the unprofitability of passenger rail in the U.S. is a product of its low population density. Rail has high fixed costs that are paid for by high volumes of passengers in areas with high population density, but are much harder to justify on low traffic routes. As one critic in a carefully fact based critique observes, passenger rail service in other countries is also most profitable in areas with high population density:

Consider Japan. Three private companies operate trains on the main island, Honshu, and make money. But all three companies that operate on the other islands lose money and are regularly subsidized. . . . France has one high-speed train that makes money—between Paris and Lyon—and the rest lose money. Spain’s and Germany’s high-speed rail have done nothing to reduce car rides, but, instead, have cut into the market share of buses.

Market Share

Unless the comfortable and scenic trip across the country is the destination, this doesn't make any sense. This is why in 2019, Americans traveled an average of 15,000 miles by automobile, 2,100 miles by plane, 1,100 miles by bus, 130 miles by walking and bicycle, 100 miles by intracity rail, and about 20 miles per person by intercity Amtrak rail service.

Outside the Northeast Corridor line service, as measured by passenger trips, about 18% is on short-haul corridors in California, about 5% is in New York State between Niagara Falls and New York City via Albany and Buffalo, and about 5% is on routes from New York City to Harrisburg, predominantly through Pennsylvania. This leaves about 34% of Amtrak trips outside of the Northeast Corridor and conventional routes in New York, Pennsylvania and California.

Environmental Impact

Amtrak is more energy efficient, consuming half as much energy per passenger mile as travel by personal passenger car, is 35% more energy efficient than traveling by bus, and is 40% more energy efficient than traveling by plane. But, these benefits are largely confined to its Northeast Corridor service. A study comparing Amtrak service to intercity bus service found that:

Excluding the Northeast Corridor, where Amtrak operates electric locomotives, the average impact of scheduled intercity motorcoach service on air quality is lower than the impact of Amtrak service. Average per-passenger emissions of particulate matter and nitrogen oxides are approximately 80% lower for motorcoach trips than for Amtrak trips, and average emissions of volatile organic hydrocarbons are approximately 90% lower.

Passenger Safety

Amtrak has about the same number of deaths per passenger mile as commercial bus service, which is much less safe than traveling by air (by at least a factor of thirty), but about 15 times safer than traveling in one's own personal car.

3 comments:

Amtrak should drop all cross country routes.

Amtrak should build real high-speed (300+ km/hr) rail between Boston and DC.

Paris to Marseille

750km in 3:20 hours

TGV

Boston to DC

704km in 6:50 hours

Acela

@DaveBarnes I totally agree.

Post a Comment