Overview

South Korea has the lowest total fertility rate in the world from rates typical of poor third-world countries in 1960, shortly after the Korean War (see also here). The fertility rates are lowest in urban area and are almost double in the most rural provinces (see also here).

South Korea also has among the oldest ages of first marriage for men and for women, and very high ages of a woman giving birth for the first time. The rates of out of wedlock births in South Korea are extremely low.

High education and housing costs, and the relatively good life of unmarried childless women compared to married women in the eyes of many young women, are important factors in the shift, as is the firm commitment to not having children without getting married.

South Korea has a dramatically declining abortion rate (something that was common but illegal and subject to misdemeanor penalties prior to 2021, but was not rigorously enforced as South Korea underwent its demographic transition).

Contraception in South Korea is heavily biased towards condoms and away from oral contraceptives, although oral contraceptive use if rising.

Birth Rates In South Korea

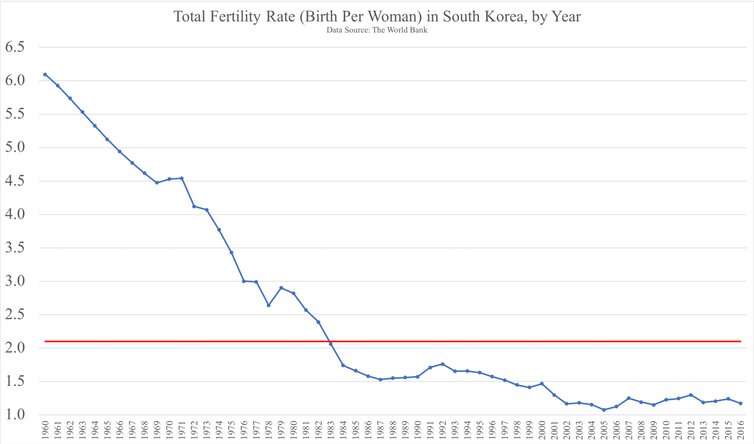

South Korea’s total fertility rate in 2020 was 0.84 births per woman—the lowest figure in the world and well below the replacement-level rate of 2.1. . . .South Korea experienced a rapid demographic transition after the Korean War, triggered by the country’s explosive economic development in the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1990s, South Korea had gone from being one of the poorest nations in the world to one of the most advanced, prosperous nations. But over this same period, increased prosperity and influential family planning policies caused a sharp decline in South Korean birth rates from 6.1 children per woman in 1960 to around 1.6 by 1990.

(Source)

The number of expected babies per South Korean woman fell to 0.84 in 2020, dropping further from the country’s previous record low of 0.92 a year earlier. . . . That is the lowest among over 180 member countries of the World Bank, and far below 1.73 in the United States and 1.42 in Japan. The grim milestone comes after the population fell for the first time ever last year. . . . The government has failed to reverse the falling birth rate despite spending billions of dollars each year on childcare subsidies and maternity leave support.The nation’s capital Seoul logged the lowest birth rate of 0.64.

(Source)

Causes of the low birthrate in Seoul are discussed here. Stating for example:

A clue to the question of what policy measures would be effective may be found in Sejong, a city in central South Korea that is home to about 340,000 residents.Sights encountered on the streets of Sejong are a world apart from what one would typically see in Seoul.Many of the mothers seen outside a kindergarten, who were there to pick up their children, were seen pushing a stroller or holding their younger children in their arms. The scene indicated many parents in Sejong have two or more children.In 2020, Sejong had a fertility rate of 1.28, double the corresponding figure in Seoul.The city was created in 2012, with part of the country’s administrative functions relocated there. As the infrastructure of livelihood, such as kindergartens and cram schools, began to improve in Sejong, government workers began to get married and settle down in the city.Woo Hye-jung, 43, a mother with three sons, said she came to live in Sejong four years ago. Her sons are in the third grade, in the first grade and 3 years old, respectively.When Woo lived earlier in another city, she sent her sons to a private kindergarten for a monthly fee of about 800,000 won per head. The kindergarten here, by comparison, is publicly run and free of charge.“Many mothers I know here say they wish they could have second and third children,” Woo said.Chun Joon-ok, director of the kindergarten that Woo’s son attends, said, "The burden of education fees is smaller and the competitive society is less stressful here than in Seoul.”“Sejong’s example shows that those who wish to have children and raise them can take a step forward if only there is a proper environment for doing so,” she said.

Another article notes that:

The birth rate dropped below 1 for the first time in 2018, when it reached 0.98; last year, it fell below 0.9.The decline in childbirth is continuing to pick up speed, with the birth rate hitting 0.75 in the fourth quarter of the year. The rate was particularly low in big cities such as Seoul (0.64) and Busan (0.75), where young people and unmarried people make up a large share of the population.South Korea’s total fertility rate was the lowest of any country in the world. In 2018, Korea was the only one of the 37 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to have a birth rate below 1 (0.98). The average rate in OECD member states was 1.63.There were 272,400 babies born in South Korea last year, down 10% from 2019 (302,700). The annual number of childbirths fell below 300,000 just three years after first falling below 400,000 in 2017.Korea reported 305,100 deaths last year, outnumbering childbirths by 32,700. That marked the first occurrence of natural population decline, in which there are more deaths than births.

(Source)

The "natural" ratio of boys to girls born is 1.05 so sex biased abortion and unreported infanticide has fallen to statistically insignificant levels after once being significant in Korea.

Fertility rate of Republic of Korea fell gradually from 4.19 children per woman in 1971. . . .

Number of births 358.79 thousandCrude birth rate 7 births per thousand populationMale to female ratio at birth 105 males per 100 femalesAge of childbearing 32.27 yearsNet reproduction rate 0.54 number

Fertility rates at age 15-19 years 1.38 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 20-24 years 11.58 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 25-29 years 45.78 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 30-34 years 105.49 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 35-39 years 52.91 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 40-44 years 4.65 births per 1,000 womenFertility rates at age 45-49 years 0.21 births per 1,000 women

(Source).

Impact Of Declining Births On Schools In South Korea

For comparison, the rest of East Asia and the Pacific has an average fertility rate of 1.8 children per woman. . . .From 1982 to 2016, 3,725 schools across the country closed due to a lack of students. This evens out to an average of 113 schools closing every year, per Yonhap News.According to the Korea Herald, 62.7% of the shuttered school properties were sold to real estate developers to be torn down. But that left some 1,350 schools standing, with no one to use them. . . . Data from the World Bank shows the country's annual population growth rate has fallen steadily over the last 60 years, dropping from 2.96% growth in 1961 to 0.13% growth in 2020.

(Source)

Life Expectency And Age Pyramids In South Korea, North Korea, and Japan

"While the country continues to see a low fertility rate and fast aging of the population, the proportion of its population aged between 0-14 years came to 12.3 percent, which is the same with that of Japan and about half of the global average of 25.3 percent," the UNFPA said.No country has a smaller proportion of the young population than South Korea and Japan.The proportion of people over 65 came to 16.6 percent of South Korea's overall population, sharply up from 15.8 percent a year earlier, according to the annual report.Globally, people 65 and older only took up 9.5 percent of the total population, tallied at some 7.87 billion.Japan had the world's largest proportion of elderly at 28.7 percent, slightly up from 28.4 percent in 2020, followed by Italy and Portugal at 23.6 percent and 23.1 percent, respectively.At birth, South Koreans had a life expectancy of 83 years, the world's 11th highest. While South Korean males had a life expectancy of 80 years at birth, South Korean females could expect to live 86 years.Their North Korean peers, on the other hand, had life expectancies at birth of 69 years for males and 76 for females, according to the UNFPA report.The maternal mortality ratio, or the number of maternal deaths per 100,000, came to 11 in South Korea, compared with 89 in North Korea.South Korea's overall population currently stands at 51.3 million, while that of North Korea is at 25.9 million. (Yonhap)

(Source as of April 14, 2021).

Marriage And Divorce In South Korea

(Source)In South Korea, the average cost of getting married is 230 million won (US$196,000), the country’s leading marriage consulting business, DUO Info Corporation, found in a two-year study on 1,000 newlywed couples.That is almost six times the amount the average South Korean in their 30s makes per year (US$32,900), and almost nine times what Koreans below the age of 29 make a year (US$22,152), according to Statistics Korea.Another survey by the Korea Consumer Agency in 2017 found that the basic cost for a wedding was US$40,000 if housing was excluded.And in recent years, marriage rates have fallen to their lowest level since data started to be compiled in 1970, with observers saying couples are increasingly put off by expectations that they must spend heavily on a new home and lavish wedding reception.“We can think of declining marriage rates as a result of changing values in today’s times, but we need to look at it as a combination of social issues arising from the economy, the job market and living expenses,” Park Soo-kyung, the founder of DUO Info Corporation, said in a recent interview.“Burdensome marriage and housing costs, incompatibility of work and family, and a negative social perception towards marriage” have all contributed to the downwards trend, she said.In 2018, the country’s marriage rate was five per 1,000 people, with 257,622 couples tying the knot, according to Statistics Korea. The rate has steadily declined from 1996, when the marriage rate hit an all-time high of 9.6 per 1,000 people and a record 430,000 couples got married.A study on worldwide marriage rates by the Organisation for Economic and Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2017 put China’s rate at almost 10 per 1,000 people while Japan was around five per 1,000.South Korea’s drop in marriage rates comes amid the increasing popularity of a feminist movement which has instilled negative perceptions about traditional marriages in the country. The #MeToo movement and the spycam porn epidemic have contributed to the creation of the “4B” or the “Four Nos”, in which women vow to never wed, bear children, date, or have sex.The recent hit film Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 , which centres on a married mother who confronts the social obstacles that exist in a male-dominated society, has also touched a nerve with many women.Last year, just 22.4 per cent of Korean women perceived marriage as necessary. But a decade ago, that number was 47 per cent.

The number of South Koreans getting married fell at a double-digit rate to a new low last year as people delayed or cancelled wedding plans amid the pandemic crisis while marriage is becoming an option, not a must, among young people, government data showed. The number of new marriages came to 214,000 last year, down 10.7% from a year ago, . . . The figure is the lowest since 1970, when data compilation began. The annualised decrease rate is also the steepest since the 18.9% plunge recorded in 1971. The figure also marks the first double-digit decline in 23 years and represents the ninth consecutive year of shrinkage, Statistics Korea said. . . .According to the agency’s 2020 survey, only 51.2% of people think they must get married, down 14 percentage points from 2010.The marriage data also showed that the average age of South Korean men getting married was 33.2 years last year, up 1.4 years from a decade ago. The median marrying age of first-time brides was 30.8 years, up 1.9 years over the same period.Meanwhile, the number of divorces in the country reached 107,000 last year, down 3.9% from 2019, marking the first annual drop since 2017.

(Source)

The number of divorces per marriage each year, which is a crude estimate of the likelihood that a marriage will ever end in divorce is exactly 0.500.

The divorce rate in Korea per 1,000 population peaked in 2003, after increasing fourfold in the previous twenty years, and then declined about 25% through 2012, although some of the decline was due, in significant part, to a smaller number of marriages per 1,000 people. In 2013, the number divorces per marriage was 0.357. In 2003, it was 0.551. In 2000, it was 0.360. A 2009 journal article looked at the determinants of divorce in South Korea, vaguely: gender, socioeconomic status, and life course.

Median age at first marriage in South Korea by year:

(Source)

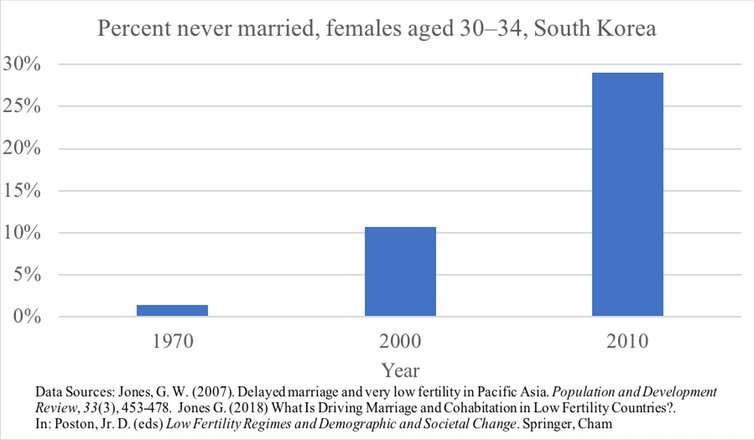

Recent reports about a sex recession among young Americans aside, the concept of dating and mating is reasonably engrained in daily life in the West. In sharp contrast, in South Korea, 40 per cent of people in their 20s and 30s appear to have quit dating altogether.Today, many refer to young Koreans as the "sampo generation" (literally, "giving up on three") because they have given up on these three things: dating, marriage and children.Although Confucian culture originated in China, many scholars believe South Korea is even more influenced by Confucianism. Confucian values emphasize the importance of marriage and carrying on the family bloodline.Getting married is considered a social responsibility. But young Koreans are increasingly leaving marriage behind.The marriage packageDemographers have used the term "marriage package" to illustrate the idea that marriage in East Asia entails much more than just a relationship between two people.In traditional Asian families, numerous intra-familial roles are bundled together, especially for women. Generally speaking, marriage, childbearing, childrearing and taking care of the elderly are linked. Hence, marriage and family roles are a package.South Korea is no exception to endorsing this cultural idea of the "marriage package."Nevertheless, Western individualistic ideologies are increasingly influencing young Koreans. Despite a strong traditional emphasis on marriage, they have begun to postpone and even forgo marriage.The average age at first marriage in South Korea jumped five years for both men and women from 1990 to 2013. Related to this is the rising number of people who stay single. In 1970, only 1.4 per cent of women between the ages of 30-34 were never married. In 2010, that percentage increased to almost 30 per cent.For women, marriage is not an attractive optionIn the last decade, The Economist has published articles about the decline of Asian marriage. One of them from 2011, "Asia's lonely hearts," discussed women's rejection of marriage in Asia and looked to gendered family roles and unequal divisions of housework as culprits.Once women decide to get married, they are generally expected to prioritize familial responsibilities. Women take on a much greater share of the housework and childcare burden and are chiefly responsible for their children's educational success.My research shows that in 2006, 46 per cent of married Korean women between 25 and 54 were full-time housewives; Korean wives, many of whom are working outside of the home, did over 80 per cent of the housework, whereas their husbands did less than 20 per cent.Women have gained more opportunities outside marriage, but within marriage, men have not correspondingly increased their contribution to housework and childcare. As a result, for many women, being married is no longer an attractive option. With diminishing returns to gender-specialized marriage for highly educated women, they are likely to delay or forgo marriage.

Since 1970, the number of singles in South Korea has increased 20-fold.Precarious economy and the overwork cultureAnother important reason young Koreans are giving up on dating, getting married and raising kids is the growing economic uncertainty and financial hardships. Many young Koreans work at precarious jobs, with low pay and little job and income security.Moreover, the culture of long working hours prevails in South Korea. Among the OECD countries, South Korea has the longest work hours.In 2017, Koreans worked an average of 2,024 hours per year, 200 hours less than they did in the previous decade. To put this number into perspective, Canadians worked 300 hours less a year than Koreans and the French, who are even better at work-life balance, worked 500 fewer hours.Recently, the South Korean government has passed a law which cut the maximum weekly hours to 52, down from 68, hoping that Koreans could still have some personal life after work.Lowest fertility rate in the worldIt is rare for single women to have children: 1.5 per cent of births were to unmarried mothers in Korea, as compared to the overall OECD average of 36.3 per cent. Therefore, there are real consequences of marriage forgone.

In Korea, the average births per woman were slightly above one in 2016, down from 6.1 in 1960 and 4.5 in 1970.South Korea is among the countries with the lowest fertility in the world. Countries need about 2.1 children per woman to sustain their population. In Korea, the average births per woman were slightly above one in 2016.Birth rates are extremely low. However, people are living longer. South Korean women will likely soon have the highest female life expectancy; South Korean women born in 2030 are expected to live longer than 90 years. Therefore, the Korean population is ageing rapidly.A shrinking population will create a labour crisis, limiting economic development. The New York Times called this demographic doom "South Korea's most dangerous enemy."The Korean government, attempting to increase birth rates, enforced a policy that all the lights in the ministry's building should be turned off at 7 p.m. sharp once a month, with the hope that employees would get off work early and go home to make love and more importantly, babies.But will forcefully switching off lights work? Maybe changing the culture of long working hours and abolishing gendered work and family roles would be more effective.There are like additional reasons behind the rise of the sampo generation in Korea, but young people's job precarity, the overwork culture and a lack of equal divisions of labour at home are vital issues.In South Korea, Valentine's Day is generally a big deal, and it is one of many holidays celebrating love. It would be great if young South Koreans could "afford" dating and family lives so they can get into the celebrations.

Abortion and Contraception In South Korea

Abortion in South Korea was decriminalized, effective 2021, by a 2019 order of the Constitutional Court of Korea.From 1953 through 2020, abortion was illegal in most circumstances, but illegal abortions were widespread and commonly performed at hospitals and clinics. On April 11, 2019, the Constitutional Court ruled the abortion ban unconstitutional and ordered the law's revision by the end of 2020. Revisions to the law were proposed in October 2020, but not voted on by the deadline of 31 December 2020.The government of South Korea criminalized abortion in the 1953 Criminal Code in all circumstances. The law was amended by the Maternal and Child Health Law of 1973 to permit a physician to perform an abortion if the pregnant woman or her spouse suffers from certain hereditary or communicable diseases, if the pregnancy results from rape or incest, or if continuing the pregnancy would jeopardize the woman's health. Any physician who violated the law could be punished by two years' imprisonment. Self-induced abortions could be punished by a fine or imprisonment.The abortion law was not strongly enforced, especially during campaigns to lower South Korea's high fertility rate in the 1970s and 1980s. As the fertility rate dropped in the 2000s, the government and anti-abortion campaigners turned their attention to illegal abortions and the government stepped up enforcement of the abortion law in response.Sex-selective abortion, attributed to a cultural preference for sons, is widespread. Despite a 1987 revision of the Medical Code prohibiting physicians from using prenatal testing to reveal the sex of the child, the ratio of boys to girls at birth continued to climb through the 1990s. The 1987 law was ruled unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in 2008. . . .Using a 2005 survey of 25 hospitals and 176 private clinics, one study estimated that 342,433 induced abortions were performed that year (about 330,000 of them illegal), which would imply an abortion rate of 29.8 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44. The rate was higher among single women than among married women. The Ministry of Health and Welfare estimated that 169,000 induced abortions were performed in 2010. Other researchers, including Park Myung-bae of Pai Chai University, estimate that there may be as many as 500,000 or 1 million abortions per year. . . .According to more recent estimates by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, the number of abortions performed per year was estimated to have declined to 50,000 in 2017.

(Source)

The number of abortions estimated to have been performed in South Korea stood at around 50,000 in 2017, sharply down from the past as more women use birth control, a report said Thursday.According to the report by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, the abortion rate for fertile women reached 4.8 percent in 2017, compared to 29.3 percent in 2005 and 15.8 percent in 2010.The report estimated that 49,764 procedures were performed in 2017, compared with 342,433 in 2005 and 168,738 in 2010.The report was based on a survey conducted on a total of 10,000 women aged between 15 and 44, the first nationwide fact-finding survey in eight years.Under South Korean law, abortions are illegal unless there are extenuating circumstances such as the unborn baby posing a serious health risk to the mother. Pregnancies resulting from statutory rape or incest are also subject to exceptions.The institute said more women are using birth control and emergency contraception, often referred to as abortion pills.The percentage of men using condoms came to 74.2 percent in 2018, sharply up from 37.5 percent in 2011, a separate report showed. The rate of women using oral birth control pills more than doubled from 7.4 percent in 2011 to 18.9 percent in 2018.The institute said only 12.7 percent of women who had an abortion used some kind of birth control at the time of conception.The report said 46.9 percent of women who opted to end their pregnancy were unmarried, followed by 37.9 percent for married women and 13 percent of women in common law marriages."The number of abortions is gradually decreasing, but many women are still exposed to unwanted pregnancies," the report said, citing the importance of proper sex education and usage of birth control.The survey, which had been conducted every five years, was discontinued in 2010 when the government enhanced its crackdown on artificial abortion as part of efforts to boost the low birthrate.The report comes as estimates by the medical sector and the government of the number of terminations carried out in the country vary greatly.There are still heated debates over the balance between the right to life and women's self-determination.More than 75 percent of the surveyed women said the law on abortion should be amended. The current law stipulates a prison term of one year and a fine of less than 2 million won (US $1,780) when women receive an abortion.

(Source as of February 14, 2019)

According to a 2015 UN report, it was found that 78.7% of South Korean women (who were married/in unions and between the ages of 15-49) used some form contraception. The most common methods were condoms (23.9%), male sterilization (16.5%), IUDs (12.6%), the rhythm method (9.7%) and female sterilization (5.8%). Meanwhile, the usage of birth control pills by South Korean was very low, with estimates ranging between 2% and 2.8%.Contraceptive adoption also varies by age. For example, in 2016, it was found that about 32% of unmarried South Korean women who were 19 years old used birth control. Meanwhile, about 56% of unmarried South Korean women who were 28 years old used birth control.While condoms are the most common form of contraception, intra-uterine devices (IUDs) have become more common. Some people have reported that unmarried women may feel discouraged from getting them, since they are thought to be "for married women." However, other reports share that many clinics provide IUDs, and there are multiple IUD options available (i.e., copper, Mirena, Skyla).Many men and women underwent the forced sterilization programs of the 1970s and 1980s.

(Source)

Birth Rates In North Korea

According to data from Statistics Korea, the South Korean National Statistical Office, the population of North Korea in 2019 stood at 25.25 million. The UN estimated that the fertility rate in North Korea between 2015 and 2020 was 1.91 children per woman of childbearing age and trending downward each year, and lower than the rate of 2.0 for the previous five-year period.The North Korean economy has been devastated by international nuclear sanctions and the closure of the border and suspension of all trade with China since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic in Jan. 2020.RFA previously reported that the government has been telling the people to prepare for conditions worse than the 1994-1998 famine, which killed millions of people, as much as 10 percent of the North Korean population by some estimates. . . .

A report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA) said that North Korea’s current fertility rate of 1.9 is lower than the world average of 2.4 and lower than the Asia-Pacific region’s rate of 2.1, which is also the rate needed to maintain a country’s current population. North Korea ranked 119th out of 198 countries listed in the report.

(Source)

No comments:

Post a Comment